IT WAS GOOD. AND HARD. AND FAST.

Monday, March 21, 2022 at 02:05PM

Monday, March 21, 2022 at 02:05PM Editor's Note: Every now and then, it's good to hit the PAUSE button. This week is one of those times (as in, Stop the world - I want to get off). So here's a special, unvarnished missive from The Autoextremist, and a look inside his incomparable high-octane life. Enjoy! -WG

By Peter M. DeLorenzo

Detroit. I am the passenger. I am a Technicolor Dream Cat riding this kaleidoscope of life. I’ve seen some things, indeed, more than most. Magic things. Loud things. Fast things.

I once looked up at a ghostly tornado finger drifting overhead in Flint. It was ominous and beyond scary. A lot of people died that day too. But then, a few years later, I saw my first 707 hanging in the sky. It was majestic and powerful. And the Jet Age was on.

I got introduced to horsepower, side pipes and chrome, and I happily got sucked in. Corvettes and 409s, GTOs and Starfires. And Sting Rays. Forever Sting Rays. And in the midst of all that, I bought and rebuilt a Bug go-kart, had the Mac 6 engine rebuilt and hopped-up, painted it bright orange, and spent one summer terrorizing our neighborhood. I dubbed it the Orange Juicer Mk 1, and found out how fast 60 mph felt that low to the ground. It was everything, all the time.

It was good. And hard. And fast.

Woodward wasn’t just a thing. It was Life. In 0 to 100 bursts. It all came alive at night. Open pipes, rumbles and roars, dares and boasts. The drive-ins smelled like burning rubber and French fries. Girls leaned and preened. Boys slouched and crouched. To get a better look. Riding shotgun with my brother, it was a world that called me.

From there, it was riding with The Maestro, Bill Mitchell – our neighbor – in the original Sting Ray racer, thinking it was normal and knowing it was not. But I soaked it all in anyway, and it was just the beginning. There were Mako Sharks, Monza Super Spyders and GTs; and XP-700 Corvettes and XP-400 Pontiacs. And on and on. It was all stunning to look at. And be in. The grass was greener and the sky was bluer, and the sounds were intoxicating.

It was good. And hard. And fast.

And then came the Cobras. All lithe and tiny next to the Corvettes. And a new kind of fast. Blistering, neck-snapping fast. A two-car-length jump off the line fast. Open-top roadsters lurking for a fight. It was the smell of English leather and burning tennis shoes when running the Cobras in the cool of the night. And believe me, there was nothing else like it.

And then road racing came calling. My brother Tony’s driver school at Watkins Glen in June of ’64. In a Tuxedo Black Sting Ray that had been personally massaged by Zora and his troops, complete with straight pipes to install when we got there. Riding on Goodyear Blue Streaks the whole way. The Glen Motor Court beckoned, but the track was the thing. That Sting Ray barked and blurted out speed, and Tony was the fastest man there. There was no turning back at that point.

It was good. And hard. And fast.

Next up was a “A” Sedan Corvair that we flat-towed all over hell and back. Starting out at our local Waterford Hills raceway, and then on to Nelson Ledges, Mid-Ohio, Lime Rock, Vineland, Grayling and even a 12-Hour endurance race at Marlboro, Maryland. But that was just the pre-game.

The real stuff was coming in 1967. We ordered what turned out to be the first of just 20 427 L88 Corvette Sting Rays built that year. I remember when we went to Hanley Dawson Chevrolet in Detroit to see the bad-ass Sting Ray for the first time. It had just been unloaded off the truck and it was stunning. We hopped in it just to see, and suspicions were conformed: It was a wild, unruly beast. We dismantled it over a weekend and had a roll bar welded-in, installed a set of American Torq-Thrust racing wheels and bolted-on some OK Kustom headers. We added a few other tweaks and we were off to our first SCCA Regional race in Wilmot Hills, Wisconsin. In “A” Production. There was a 427 Cobra there, too, but it was no match for our Super Sting Ray. Tony won going away. And then it was off to the races, literally: Mid-Ohio, Road America, Blackhawk Farms, Nelson Ledges, Watkins Glen, Daytona.

It was good. And hard. And fast.

And then everything changed. Owens/Corning Fiberglas became our sponsor. And the races got bigger. Twenty-two straight wins in “A” Production, with twelve 1-2 finishes with teammate Jerry Thompson, who would go on to win the National Championship in ‘69. Then it was the major endurance races with GT class wins at Daytona, Sebring and Watkins Glen. And the Trans-Am series in 1970 with Camaros, and in 1971 with ex-Bud Moore factory Mustangs. And finally, the infamous Budd-sponsored Corvette in 1973, with Tony sitting on the pole at Sebring for the all-GT 12-hour race that year.

They were fleeting moments in time, but they were unforgettable. Pouring a bucket of water over my head after gas spilled all over me during a pit stop at Marlboro. Waking up in the cab of our semi on the Ohio Turnpike in the middle of the night on the way to Lime Rock only to see that my brother was fast asleep as we were running diagonally off the left shoulder and headed for the median. I yelled. We made it. But that was just the way it was back then. No sleep for days on end getting the cars ready – to the point of exhaustion – only to then have to load up and drive to the next race. It was relentless.

Then there was the infamous Pontiac street race in 1974. It was a dubious track at best, with haybales and guardrails offering little protection for the drivers, or the crowd. Tony was passing a slower car during the race and the driver moved over on him. The move forced Tony into some haybales, turned him sideways, causing his Corvette to barrel roll 20 feet in the air taking out a light pole. That impact with the light pole saved him from going into a spectator area of at least one hundred people. I was a fair distance away when I saw a flash of his car going end-over-end (after the light pole impact) down the straightway on Wide Track avenue. I sprinted to get there, only to see the car burst into a fireball. I arrived to see my brother laying on the ground. He had gotten out in time, barely a moment before the car burst into flames. It was only later that we found out that a guy who was keeping the car in Florida in-between Daytona races had removed the check-valve in the fuel cell “to save weight.” Idiot.

Needless to say, that was a dark day, especially since a reporter at the event called one of my dad’s GM PR staffers – my mom and dad were at an outdoor party with his entire PR staff – and informed him that Tony had been killed in Pontiac. (He never saw Tony get out of the car.) My dad’s right-hand man informed my parents that they had to go to St. Joseph Mercy Hospital in Pontiac immediately. They feared the worse, of course. So that was me at the hospital seeing the ashen look on my parents’ faces when they arrived. I took them to see my brother on a gurney in the hallway; he was alert but battered and extremely sore. My parents were relieved, and so was I.

But that was only part of my ride on this kaleidoscope of life. There was the time we built a prototype ’69 L88 Corvette roadster (in black/black, of course) called the “Daytona GT” with the intention of selling customer versions. It was basically one of our racing cars equipped with a few more comfort options. We even got display space at Cobo Hall during the Auto Show to show it off. But the pressures of running the racing team meant that the project was shelved. The Corvette was eventually rebuilt to fully race-prepared OCF racing team specs, given a psychedelic paint job and sold to a German Lufthansa pilot who used it to terrorize local and national racing events over there. But before that all happened, I was tasked with keeping it in running order and exercised. Needless to say, I relished that assignment and I happily terrorized the area with open headers on my “exercise” jaunts.

It was good. And hard. And fast.

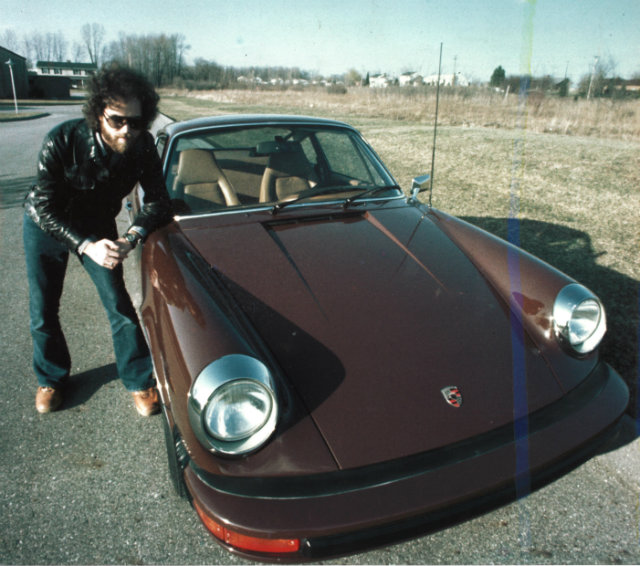

Then I veered off on my own and became enchanted with the Porsche 911. I bought a used ’75 911S and proceeded to drive that car all over hell and as fast as it would go. I spun-out once going 100 mph on a two-lane road because unbeknownst to me the shoulder had just been graded and there was dirt all over the road in a left-hand sweeper. I came to a stop with the rear wheels right on the edge of a 20-foot drop. And then there was the infamous late-afternoon run from East Lansing to Ann Arbor that I did flat-out, rarely going below 100 mph the entire distance. I made it to my destination in just under 30 minutes, door-to-door. And it is just as vivid for me today as it was when I did it. Fleeting moments indeed.

And then there was the time during my ad career that I spent shooting commercials at the Nurburgring Nordschleife, for a full week. We were short performance drivers, so I spent the week assisting with the driving while tearing around the circuit for the filming. And if that wasn’t special enough, NATO jets were using the wide-open terrain to practice high-speed, low-level maneuvers. How low? We could see the helmet marking on the pilots as they banked over us at tree-top level. It was a week-long orgy of speed that I will never forget.

The point of all this? I’m still a Technicolor Dream Cat riding this kaleidoscope of life. This column gave you fleeting glimpses of some fleeting glimpses. There’s plenty more to tell and a long, long way to go. And I'm not close to being finished.

It was good. And hard. And fast. Indeed.

And that’s the High-Octane Truth for this week.

The Autoextremist. March 1976, East Lansing, Michigan. (J. Geils called; he wants his look back.)

The Autoextremist. March 1976, East Lansing, Michigan. (J. Geils called; he wants his look back.)