THE CERV I AND CERV II: A TRIBUTE TO GM'S TRUE BELIEVERS.

Monday, December 18, 2017 at 01:44PM

Monday, December 18, 2017 at 01:44PM Editor-in-Chief's Note: I decided to leave the story of the Chevrolet Engineering Research Vehicles - CERV I and CERV II - up until we're back in January. Why? Because it's simply more compelling than anything going on in contemporary racing at the moment. Yes, I'm encouraged by the new bodywork changes and other regulations for IndyCar in 2018, with the renewed emphasis on the driver. And I am thrilled about the growing momentum in IMSA - kudos to Scott Atherton and the entire crew at IMSA for persevering - but I find the rest of the racing world - except for MotoGP - to be decidedly downbeat. My early interest in Formula E has slipped away because the visceral appeal of those cars is nonexistent. Yes, I get it, drivers will drive anything if they can get a ride, in fact, as I've said repeatedly - drivers will drive through a shit storm for Twinkies they want to do it so bad - but that doesn't make it right, or interesting. The manufacturers are all lining up to participate because they can sync their involvement in Formula E with their R&D budgets. And good for them. But as Samuel Goldwyn once famously said, "Include me out." As for F1, it barely holds my interest. The lackluster sound of those cars is simply inexcusable. Pinnacle of the sport? Not in its current configuration, and I'm not optimistic about the future engine rules being discussed either. As for NASCAR, I am pretty much finished writing about that particular genre of motorsport. I have the utmost respect for the talented drivers, engineers and technicians, but the France family - led by the serially incompetent Brian France - is running NASCAR right into the ground. Besides, in the last column I wrote about NASCAR in 2017 - "REMAKING THE NASCAR SCHEDULE IN AN ERA OF REDUCED EXPECTATIONS" - I said all that needed to be said. In fact, I vow to not write about NASCAR in my Fumes column in 2018 unless something compels me to do so. We will continue to mention NASCAR in "The Line" next year, but that's about it. And finally, once again a big "thank you" to all of the people who work behind the scenes at race tracks all across the country and make it possible for the races to go off without a hitch. The racing simply wouldn't happen without you. And of course a huge "thank you" goes out to the corner workers, again, the racing wouldn't happen without your dedicated and tireless efforts. I'll see you back here next year. -PMD

By Peter M. DeLorenzo

Detroit. If any of our readers follow me on twitter (@PeterMDeLorenzo), you'd know that in the past few weeks I've been tweeting about the Chaparral racing cars and GM Engineering's intimate involvement in that fabulous program. I will probably continue to do so in the coming weeks and months, but this week I wanted to devote some time to the Chevrolet Engineering Research Vehicles, the CERV I and CERV II.

The CERV program originated with Corvette icon Zora Arkus-Duntov, who envisioned it as a platform for engineers to use in order to develop Chevrolet - specifically Corvette - body, chassis and suspension systems. The CERV I was developed between 1959 and 1960 as a functional mid-engine, open-wheel, single-seat prototype racing car. The bodywork was designed by industry legends Larry Shinoda and Tony Lapine.

The CERV I was originally equipped with a fuel-injected 283 cu. in. 350HP small block V8 that weighed only 350 lbs. Intensive use of aluminum and magnesium engine components saved more than 175 lbs. from previous Chevrolet V8s. The body structure was constructed out of fiberglass and weighed only 80 lbs. The body structure was attached to a rigid 125 lb. chrome-molybdenum tube constructed frame, welded in a truss-like configuration. Combining these lightweight components contributed to the CERV I's weight of 1,600 lbs. The 96-inch wheelbase chassis features a four-wheel independent suspension, uses independent, variable rate springs with shock absorbers and stabilizer bar in the front, and multilink, variable rate springs, with double-acting shock absorbers in the rear. The wheels are cast magnesium alloy. Steering is recirculating ball type with 12:1 ratio.

The brake system on the CERV I uses front disc/rear drum, with a two piston master cylinder to eliminate the chance of complete brake failure. Fuel is delivered via two rubber bladder fuel cells (20 gal. total capacity).

At one point Duntov refitted the CERV I with a 377 cu. in. aluminum small block, an advanced Rochester fuel injection system and Indy-style tires and wheels. (That 377 cu. in. small block V8 became the mainstay in the Corvette Grand Sport racing program.) To match this mechanical updating, Shinoda redesigned its streamlined body structure for greater aerodynamics. Top speed for the CERV I was 206 mph, achieved on GM's circular 5-mile test track at its Milford, Michigan, Proving Grounds.

Excited by its impressive performance potential, Duntov had his eye on bigger things for the CERV 1 - including racing in the Indianapolis 500 - but due to the AMA (Automobile Manufacturer’s Association) ban on manufacturer-sponsored racing at the time - which GM painfully adhered to - the closest Duntov could get to a major showcase for the car was when he drove the machine in a series of demo laps at the U.S. Grand Prix in 1960.  (RM-Auctions)

(RM-Auctions)

The CERV 1. (RM-Auctions)

(RM-Auctions)

The CERV I appeared in the international racing colors - white with blue - assigned to the United States.

The next-generation Chevrolet Engineering Research Vehicle - the CERV II - was conceived early in 1962, developed over the next year and built under Duntov’s direction between 1963 and 1964. By the time it was finished, Duntov envisioned the CERV II as a possible answer to the Ford GT40 racing program. At this point it was also in Duntov's mind to develop a separate line of racing Corvettes to sell, an idea that was later rejected, of course, by GM management. Duntov wanted the CERV II to showcase future technologies as applied to a racing machine.

Chevrolet General Manager "Bunkie" Knudsen wanted to get back into racing so the CERV II was planned for the international prototype class with a 4-liter version of the Chevrolet small block V8. Knudsen has been given strict orders to stay out of racing by upper management at GM, but obviously that didn't dissuade Duntov and his team. Construction was started on the CERV II almost at the same time that the "no racing" GM management edict came down.

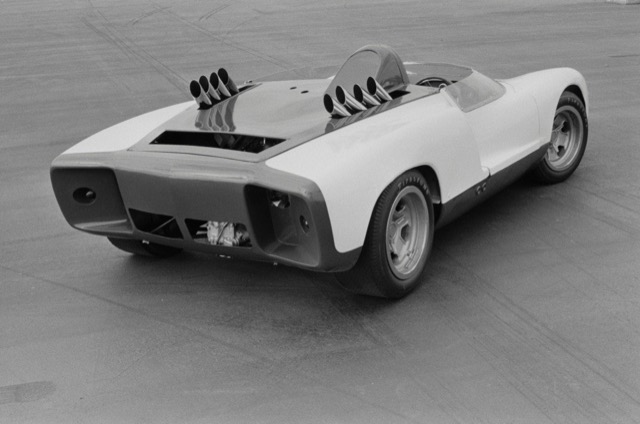

As with CERV I, the body was designed by the team of Shinoda and Lapine. The chassis of the CERV II consisted of a glued-together steel and aluminum monocoque with a steel sub frame to carry the suspension and engine. It was powered by a Hilborn fuel-injected, overhead cam, 377 cu. in. aluminum small block V8 with a 10.8 compression ratio and 500HP. By 1970, the CERV II ran a 427 cu. in. ZL-1 V8 with 550HP. Titanium was used for the hubs, connecting rods, valves, and exhaust manifolds helping to bring the total weight of the machine below 1400 lbs.

The CERV’s II engineering of the drive system and torque converter arrangement was handed over to GM’s engineering team and it turned out to be its most fascinating development. The result? An advanced all-wheel drive system using two torque converters. This marked the first time that anyone had designed a variable power delivery to each end of the car, which varied according to vehicle speed. The very wide wheels carried experimental low profile Firestone tires mounted on specifically constructed Kelsey-Hayes magnesium wheels. The ventilated disc brakes were mounted outboard, with the Girling calipers widened to accept the vented rotors.

The CERV II was very quick: 0-60 in 2.5 seconds with a top speed of 190+ mph. During its extensive development Jim Hall and Roger Penske were among the top drivers who wheeled the CERV II.

The plan to use the CERV II as The Answer to the Ford GT40 program ended up being killed by GM management, as was their wont. The CERV II was used as a research tool for a mid-sixties super Corvette program that was also cancelled by management. Never raced, the CERV II ended as a show and museum piece, a tribute to the True Believers at GM Design and Engineering.

Editor-in-Chief's Note: Thank you to the GM Heritage Center for the details on the CERV I and CERV II. -PMD (GM)

(GM)

The True Believers at GM Engineering stand proudly by the magnificent CERV II at its roll out at the GM Technical Center in Warren, Michigan. (GM)

(GM)

The CERV II photographed at the famous "Black Lake" at the GM Proving Grounds in Milford, Michigan. (GM)

(GM)

An inside look at the CERV II.

Editor-in-Chief's Note: As part of our continuing series celebrating the "Glory Days" of racing, this week's images come from GM. - PMD

(GM)

(GM)

GM Technical Center, Warren, Michigan, 1957. Zora Arkus-Duntov being wheeled out for the maiden test run of the Corvette SS racing car. GM had a short test track on the Tech Center grounds that saw extensive use.

(GM)

GM Technical Center, Warren, Michigan, 1957. The Corvette SS racer being finished before being shipped down to Sebring, Florida, for its racing debut in the 12-Hour race.