Editor-in-Chief's Note: Now that the entire racing world has been put on hiatus, it gives us a chance to take stock of where we are, and where we've been. As I've stated many, many times before, racing in the 1960s in North America and around the world was different. Everything was new, and the idea of going faster was on an upward trajectory. The technical developments in aerodynamics, tires, suspension, brakes and power were accelerating at a furious pace, but the sport was still populated by backyard geniuses and groups of committed people who came together to go racing. In sheds in North Carolina and gas stations in Florida; a talented group of hot-rodders in a warehouse in Venice (Calif.); brilliant, self-trained mechanics in Indianapolis; a creative genius in West Texas; a lanky visionary in Southern California; the immensely talented engineers in Detroit; and the countless maverick engineers and mechanics in England and Europe were all in the pursuit of speed wherever it took them, in places as diverse as the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, Brands Hatch, Le Mans, Monza, Monaco, Watkins Glen, Laguna Seca, Road America and countless other venues. Until the sport was swallowed whole by the advancements in technology in the late '70s and it became a constant game of restrictions in order to manage the speeds being achieved, groups of people came together to go racing, flat-out. This was long before the racing conglomerates that we see today, of course, because it was a different time and a different era to be sure. Was it better? In some respects, yes, and in others, no. The pursuit was glorious, the dangers and deaths were not. The following series highlights one of those memorable stories and captures a fleeting moment in time when a group of tremendously talented volunteers came together and made racing history. We have run this series before, as longtime readers know, but every week we get new readers who are not familiar with what went on back then. And as people have commented to me many, many times, it is worth the read. -PMD

By Peter M. DeLorenzo

© 2020 Autoextremist.com

Detroit. My brother Tony's meteoric racing career, which started out at a SCCA driver's school at Watkins Glen in 1964 ("Part I") and transitioned into racing a 427 L88 Corvette in "A Production" in the Central Division of the SCCA, and then on to the special sponsorship relationship with Owens/Corning Fiberglas that began in the summer of '68 ("Part II"), was a rocket ride. And for those of us who lived it, it all went by in a blur. Now, we pick up the inside story of the Owens/Corning Fiberglas Corvette Racing Team right where we left off last week, in "Part III."

After recording impressive victories in the FIA GT class at the the 1969 Watkins Glen 6 Hour (7th overall, 1st in GT +2.5L), the 1970 Daytona 24 Hour (6th overall, 1st in GT +2.5L) and the 1970 12 Hours of Sebring (10th overall, 1st in GT +5.0L), the Owens/Corning Fiberglas Corvette Racing Team had gone from being a backyard operation to a force to be reckoned with in FIA endurance racing in just 2-1/2 years. And this was on top of the team's domination of SCCA racing, which culminated with a National Championship for Jerry Thompson at the Runoffs in 1970.

But even though the team was just hitting its stride and despite all of the success that the team had delivered for its sponsor, change in the racing business is inevitable. And change in this case meant that the 1971 Daytona 24 Hour race would mark the end of the relationship between Owens/Corning Fiberglas Corporation and our racing team. The company had been very successful leveraging the high-visibility racing effort of our Corvette team to OEMs - particularly to GM - and to customers and employees at the races, thanks to PR man Roger Holliday's efforts. There was no question that the team had put OCF on the map. And Tony and Jerry contributed to the success of the relationship by making appearances at Owens/Corning Fiberglas plant facilities all over the country. So some executives at OCF headquarters may have concluded that the company had gotten what they wanted out of the sponsorship and didn't need to do it anymore. Or perhaps certain executives in Toledo were irritated by the fact that we added a two-car Trans-Am Camaro effort for the 1970 season to run against the factory entries in our "spare" time. At any rate, Daytona would mark the end of the road for one of the most visible sponsorship relationships in American racing.

There would be other things different about the team before the looming endurance marathon at Daytona too. For one thing, Jerry Thompson and Jim McIntosh personally assembled the 427 cu. in. L88 racing engines in Jerry's garage. Interesting side note? The cars showed up at Daytona with bright yellow engine blocks and heads. Why, you might ask? Well, it seems that there were several brand-new cans of yellow Rust-Oleum on the shelf in that garage, and when it came time to finish off the engines, convenience won out!

Despite the bad news that this race would mark the end of the Owens/Corning Fiberglas deal, the team arrived and unloaded at Daytona ultra-prepared and optimistic about its prospects for the long grind ahead. Don Yenko would be driving with Tony in the No. 11 Owens/Corning Fiberglas Corvette and Jerry would be driving the No. 12 OCF team car with John Mahler. And the team made a statement right from the get-go by being fastest of the GT +2.5L runners in pre-race practice. In qualifying, the outright speed of the OCF cars was evident. Tony qualified on the pole with a lap of 1:57.19 and Jerry qualified with a 1:59:00 flat to make it a 1-2 for the Owens/Corning Fiberglas Corvette Racing Team in GT+2.5L, ninth and tenth overall, in an impressive field.

The very front of the grid was dominated by the fastest prototype cars, including the factory Porsche 917 Ks and Ferrari 512Ms. But the fastest of the fast was Mark Donohue (No. 6 Penske-White Racing No. 6 Sunoco Ferrari 512M), who would put his impeccably-prepared, Sunoco blue Ferrari (that he would share with David Hobbs) on the pole with a blistering lap of 1:42.42. And then there were the other competitors in GT just itching to dethrone the OCF team, including David Heinz and Or Costanzo in the No. 57 Corvette 427 L88; and John Greenwood, Allan Barker and Dick Lang in the No. 50 Corvette 427 L88. The race was shaping up to be a real slugfest.

All of the competitors got through the starting melee in good shape and then it was down to business in America's longest racing day. Mark dueled with Pedro Rodriguez (No. 2 John Wyer Automotive Engineering Gulf Porsche 917 K, co-driven by Jackie Oliver) and those two set the early pace at the front, while the OCF Corvettes settled into their planned pace. But in endurance racing, as racers well know, sometimes things can change in an instant. Very early in the race - on its 82nd lap - the No. 12 OCF Corvette broke a timing chain, which put Jerry and John out of the race. The team decided to add John to the No. 11 car, with Jerry helping to coordinate pit strategy.

By around midnight, the No. 11 OCF Corvette was leading the GT class and running a very strong fifth overall behind Luigi Chinetti Jr./Nestor Garcia-Veiga/Alain De Cadenet (No. 21 North American Racing Team Ferrari 312 P). But there were incidents; there are always incidents at Daytona. Vic Elford (No. 4 Martini & Rossi 917 K, co-driven by Gijs van Lennep) blew a rear tire on the 31 degree banking in the NASCAR Turn 4, hitting the wall hard, then going down to the flat, and then sliding back up track, hitting the wall hard again before coming to rest on the track apron. Mark Donohue arrived on scene slowing for the dust cloud, but a trailing 911 Porsche didn't slow down at all and rammed the Ferrari hard, doing major body and suspension damage. The 911 then slid off the banking and hit Elford's 917, totally destroying what was left of it. Then, as if that weren't enough, that 911 rolled eight times completely destroying itself (the driver was okay). Elford had exited his 917 moments before, avoiding catastrophe.

The No. 11 OCF Corvette pressed on, but not without issues, however. The team was battling a recurring electrical problem. The voltage regulator was failing, requiring replacement of the back half of the alternator (FIA rules prohibited replacing the entire unit). The team's electrical "department" experts - Les Talcott and Ken Wiedbusch - worked feverishly gathering spares and changing parts during pit stops. The final part needed was liberated from the team's pickup truck, which had made the journey down from Detroit. All of a sudden, it had been a long night.

As rain began to fall just after dawn, John Mahler got the call to get in the No. 11 car. John did his usual excellent job, maintaining the team's lead in GT +2.5L. But the No. 11 OCF Corvette had also developed a clutch linkage issue that required some double clutching on up-shifts. After Tony went out for his mid-morning stint, Don Yenko asked Jerry if he thought Tony could handle the clutch work. Jerry replied: "Hell, he drives the semi, I think he'll be okay!" Laughter can come at unexpected moments in the heat of battle.

During Tony's stint, however, one of the strangest incidents in the team's history occurred. As Tony exited the "horseshoe" (Turn 3) in the infield, a mysterious explosion under the car briefly knocked his feet off the pedals. There was no damage, but there was no way to explain what happened, either. Tony would later speculate that maybe one of the denizens of the infield had tossed a M80 on to the track, or something. To this day it's the one racing incident in the team's history that remains unexplained. (There were other incidents during the race, including a plane crash on take-off at the airport next to the track!)

The Rodriguez/Oliver No. 2 J. W. Automotive Engineering Gulf Porsche 917 K won the race; Tony Adamowicz/Ronnie Bucknum (No. 23 North American Racing Team Ferrari 512S) finished second; and the No. 6 Penske-White Racing Sunoco Ferrari 512M driven by Donohue/Hobbs recovered to finish third. After the No. 21 Ferrari 312 P of Chinetti Jr./Garcia-Veiga/De Cadenet encountered transmission trouble, the No. 11 Owens/Corning Fiberglas Corvette Racing Team 427 Corvette L88 driven by Tony DeLorenzo, Don Yenko and John Mahler finished fourth overall, the highest finish to date for a Corvette in major league endurance racing. After two straight days of zero sleep, the team got to see their car's number on the main scoreboard, making it worth every excruciating moment.

The reign of the Owens/Corning Fiberglas Corvette Racing Team had come to an end. It was a fleeting moment in time when wild dreams and grand expectations magically came together to power one of the most successful Corvette racing teams of all time. The team had pioneered many of the things taken for granted in today's racing when it came to image wrangling and on-site activation of racing sponsorships.

As for the often-rumored "factory" connection to the team, where everyone assumed that we were being given factory money or some such nonsense? That never happened. Despite the impressive array of GM design and engineering talent that contributed to the team's efforts on a volunteer basis, the only help we received from Chevrolet Engineering was a parts exchange arrangement. We'd break something on the track and Chevrolet Engineering would study, learn and replace it with a better part. That's how it worked. In fact, the team's on-track competition program became a living, breathing R&D program for Chevrolet that would contribute many of the improvements to future production Corvettes during that period.

But we found out the hard way that the team's glittering success in putting Corvette back on the racing map and delivering the marque's highest finish in a major endurance race didn't count for much. In fact, nine months before, when we decided to compete in the famed 1970 Trans-Am series in Owens/Corning Fiberglas-sponsored Camaros, we discovered in no uncertain terms that our "favored" relationship with the powers that be at GM and Chevrolet was well and truly over. Because the decision had already been made that Jim Hall would get the factory-supported Trans-Am deal, and we were now considered to be nothing more than just another independent racing team.

Translation? It was as if none of the success of the OCF team ever happened, or even mattered, and there would be no help coming our way from Chevrolet. It was the "thanks, and don't let the screen door hit your ass on the way out" kiss-off. We were treated so badly by a particular politician/scumbag who was in charge at the time (and who shall remain nameless) that after beating our heads against the wall during the Trans-Am series in the '70 season - where Tony delivered some very impressive finishes - we bought two of Bud Moore's factory-prepared 1970 Trans-Am Championship Ford Mustangs to compete with in the 1971 Trans-Am season.

So the win at Daytona in 1971 was not only big, it was immensely satisfying on a number of levels. Owens/Corning Fiberglas had departed, and Chevrolet may have decided that we were expendable, but we weren't finished yet.

There's more. Stay tuned for The Aftermath in Part V.

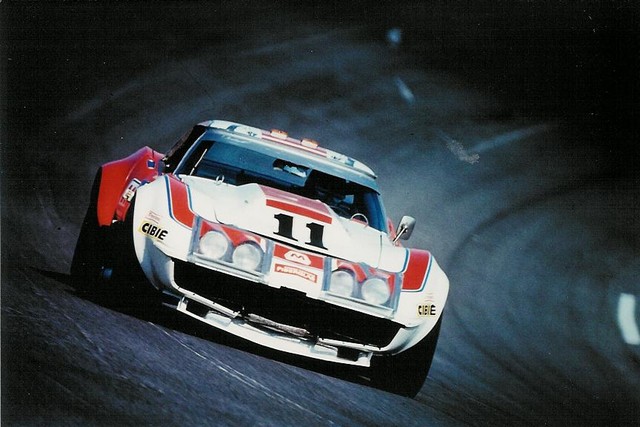

(Photo by Hal Crocker/The DeLorenzo Collection)

The No. 11 Owens/Corning Fiberglas Corvette Racing Team 427 Corvette L88 driven by Tony DeLorenzo (above), Don Yenko and John Mahler avoided on-track carnage, electrical issues and a "mystery" explosion to finish fourth overall in the Daytona 24 Hour race, the highest finish to date for a Corvette in major league endurance racing. After two straight days of zero sleep, the OCF team got to see its car's number on the main scoreboard, making it worth every excruciating moment.

(Photo by Hal Crocker/The DeLorenzo Collection)

It was ironic that in the Owens/Corning Fiberglas Corvette Racing Team's final race - the 1971 Daytona 24 Hour - the team would deliver its greatest victory.

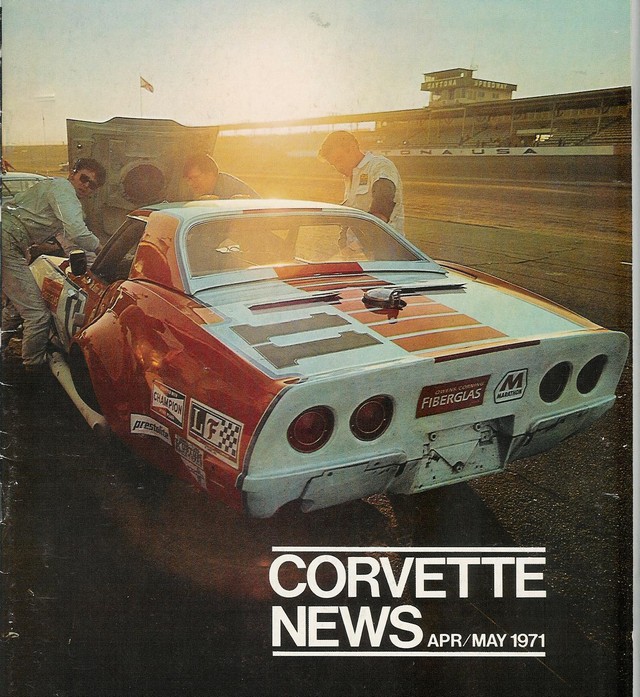

(The DeLorenzo Collection)

Tony in the No. 11 OCF Corvette at Daytona in 1971. Even though the team delivered its greatest win, Chevrolet had already decided that the team had become expendable.

(The DeLorenzo Collection)

John Mahler got the call to maintain the No. 11's lead early Sunday morning in the rain at Daytona in 1971. He delivered.

(The DeLorenzo Collection)

After finishing a sensational fourth overall and first in the GT +2.5L class at the Daytona 24 Hour, the Owens/Corning Fiberglas Corvette Racing Team celebrated together for the last time. Crewman Fred McKenna (with back turned at front of car); Roger Holliday, the ace OCF Public Relations man (red jacket with camera); Deryl Denman (looking under the hood at right); Nick Ollilla smiling on right (Nick went on to have a great career with Penske Racing); and Tony with his back to the camera (in the filthy drivers suit!).

(The DeLorenzo Collection)

When Tony DeLorenzo, Don Yenko and John Mahler (No. 11 Owens/Corning Corvette Racing Team Corvette 427 L88) finished fourth overall and first in GT +2.5L at the Daytona 24 Hour race in 1971, it was a very big deal for Corvette fans around the world and a signature moment in Corvette racing history. Here is the cover for Corvette News, which devoted almost an entire issue in celebrating the achievement. The photo, taken during practice for the race, shows Jerry Thompson (left) and “Spike” Olilla checking under the hood, with famed GM designer Randy Wittine off to the side on the right.

Editor's Note: Many of you have seen Peter's references over the years to the Hydrogen Electric Racing Federation (HERF), which he launched in 2007. For those of you who weren't following AE at the time, you can read two of HERF's press releases here and here. And for even more details (including a link to Peter's announcement speech), check out the HERF entry on Wikipedia here. -WG

Publisher's Note: As part of our continuing series celebrating the "Glory Days" of racing, we're proud to present another noteworthy image from the Ford Racing Archives. - PMD

(Courtesy of the Ford Racing Archives)

New Smyrna Beach, Florida, February 10, 1957. A crewman tends to the No. 98 Ford Thunderbird "Battlebird" that was driven by Marvin Panch in the road race held at the at the New Smyrna Beach Airport. The "Battlebirds" were Thunderbirds highly-modified with many custom road racing preparation tricks by Peter DePaolo Engineering in Long Beach, California. This particular car featured a hand-formed aluminum hood, doors, trunk, firewall and belly pans by Dwight “Whitey” Clayton and Dick Troutman. It also had a fared-in headrest and was lightened considerably. A completely new tubular chassis was fabricated and the suspension and brakes were non-stock as well. And the engine was prepared by Jim Travers and Frank Coon, before they formed the famed Traco Engineering Co. An eight-turn, 2.4-mile road course was laid out at the airport that still sits alongside U.S. Highway 1, and about 100 drivers were lured for the SCCA races. The entries included a former Indy 500 winner, Troy Ruttman, NASCAR stars Fireball Roberts, Curtis Turner, Panch and Paul Goldsmith, and a lanky Texan by the name of Carroll Shelby. The future father of the Cobra won handily in his John Edgar-owned Ferrari 410 Sport. Richie Ginther was second in a Ferrari 750 Monza, and Panch finished third.