Editor-in-Chief's Note: Now that the entire racing world has been put on hiatus, it gives us a chance to take stock of where we are, and where we've been. As I've stated many, many times before, racing in the 1960s in North America and around the world was different. Everything was new, and the idea of going faster was on an upward trajectory. The technical developments in aerodynamics, tires, suspension, brakes and power were accelerating at a furious pace, but the sport was still populated by backyard geniuses and groups of committed people who came together to go racing. In sheds in North Carolina and gas stations in Florida; a talented group of hot-rodders in a warehouse in Venice (Calif.); brilliant, self-trained mechanics in Indianapolis; a creative genius in West Texas; a lanky visionary in Southern California; the immensely talented engineers in Detroit; and the countless maverick engineers and mechanics in England and Europe were all in the pursuit of speed wherever it took them, in places as diverse as the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, Brands Hatch, Le Mans, Monza, Monaco, Watkins Glen, Laguna Seca, Road America and countless other venues. Until the sport was swallowed whole by the advancements in technology in the late '70s and it became a constant game of restrictions in order to manage the speeds being achieved, groups of people came together to go racing, flat-out. This was long before the racing conglomerates that we see today, of course, because it was a different time and a different era to be sure. Was it better? In some respects, yes, and in others, no. The pursuit was glorious, the dangers and deaths were not. The following series highlights one of those memorable stories and captures a fleeting moment in time when a group of tremendously talented volunteers came together and made racing history. We have run this series before, as longtime readers know, but every week we get new readers who are not familiar with what went on back then. And as people have commented to me many, many times, it is worth the read. -PMD

By Peter M. DeLorenzo

© 2020 Autoextremist.com

Detroit. I'm going to backtrack a bit for this installment of "The Glory Days." Last week, I covered the triumph of the Owens/Corning Fiberglas Corvette Racing Team in the Daytona 24 Hour in 1971, with Tony DeLorenzo, Don Yenko and John Mahler finishing fourth overall and first in GT in the No. 11 OCF 427 L88 Corvette. It was the culmination of an incredible run for the OCF team, having recorded impressive FIA GT Class victories at the 1969 Watkins Glen 6 Hour (7th overall, 1st in GT +2.5L), the 1970 Daytona 24 Hour (6th overall, 1st in GT +2.5L) and the 1970 12 Hours of Sebring (10th overall, 1st in GT +5.0L). Not to mention "The Streak" in SCCA National races that continued unabated in 1970, which had followed a '69 National Championship in "A Production" for Jerry Thompson. But the triumph would be the team's last as the Owens/Corning Fiberglas Corvette Racing Team, as the sponsorship ended with the 1971 Daytona 24 Hour race.

As I suggested last week, there were a number of reasons for it. Despite all of the success for the team and the spike in attention - and OEM business - delivered for Owens/Corning Fiberglas Corporation, change in the racing business is inevitable. And change in this case meant that some executives at OCF headquarters had concluded that the company had gotten what they wanted out of the sponsorship program and didn't feel the need to do it anymore. But the real reason may have been the fact that certain executives in Toledo were irritated by the fact that the team added a two-car Trans-Am Camaro effort for the 1970 season to run against the factory entries in our "spare" time. In their view there was no direct connection between the Camaro and the Owens/Corning Fiberglas product, like there was with the Corvette. Shortsightedness on their part? You could say that, especially since the explosion of the use of lightweight materials in production cars was right around the corner. But so be it.

Why and how did the team's effort in the 1970 Trans-Am season come together? Most of it was driven by Tony's desire to advance his driving career. His ultimate goal? Racing in Indy cars. And to be a part of the hottest road racing series in the world, which the 1970 Trans-Am Series was shaping up to be, seemed like a tremendous opportunity. He felt the team had more than demonstrated its capabilities and it had more than enough talent - albeit a deep reservoir of mostly volunteers - to throw elbows with the big factory teams in the 1970 Trans-Am season, so it was time to step up the program.

The first team meeting with OCF to discuss the 1970 season took place at Daytona in November of ’69 at the SCCA Runoffs. A follow-up meeting occurred in Toledo shortly after the team's return from Daytona. The decision was made to run the Corvettes in A-Production and FIA long distance races again, and that the team would prepare two 1970 Camaros and run them in the Trans Am series. Since all the OEMs would be competing in Trans Am that season, it was logical that the OCF sales promotion efforts would get the increased exposure through the program. At least that was the pitch. Not everyone at OCF was thrilled, but the added incremental funds to support the program materialized, and the two-car Camaro effort would boast the red and white Owens/Corning Fiberglas Corporate colors.

This would be a serious commitment for the team. It would turn out to be 22 races with four cars in various racing configurations (FIA, SCCA, Trans-Am), all for the princely sum of $225,000.00! Nowadays, that would almost pay for the power unit (tractor) to pull your trailer to the races. A news conference took place at Daytona in January 1970, during the 24 Hour race week, announcing that the Owens/Corning Fiberglas Corvette Racing Team would be fielding two Camaros in the 1970 Trans-Am Series.

This was not an insignificant undertaking, in fact the OCF Corvette Racing Team was strained to the max to put together the effort for the '70 Trans-Am series. Starting with two bodies in white that were ordered from the GM Norwood plant in Cincinnati through Hanley Dawson Chevrolet, the team scrambled to put two proper Camaro entries together for the upcoming Trans-Am opener at Laguna Seca. The bodies were “prime only” but came with glass and door hardware. We also acquired the sheet metal - hoods, deck lids, front fenders, etc. Jerry Thompson was getting various drawings and other information through his fellow Chevrolet Engineering contacts, and six 302 cu. in. Chevrolet V8 crate motors were obtained to begin the engine program. (The fact that Chevrolet was fielding a factory Trans Am effort with Jim Hall of Chaparral fame would turn out to be a major issue as the OCF program progressed. More on that later.)

As I pointed out last week, all of this was being done with zero help from Chevrolet, as the slimy bureaucratic Poo-Bah who was in charge of doling out Chevrolet funds to racing teams had determined that the OCF team was inconsequential, despite its prodigious success with their Corvettes. This made it more difficult, to say the least, because we were under the gun to construct two Camaros while still racing the OCF Corvettes in SCCA National races.

It did not go smoothly to put it mildly, as everything about the cars - engines, transmissions, suspension design, brakes, aero, you name it - was new and different. The full measure of the team's volunteer engineering talent from Chevrolet was challenged every step of the way, as the cars were constructed with lessons gleaned from two years of racing the Corvettes. One major lesson? We had installed roll cages in the OCF Corvettes prior to the’70 season and the improvement in chassis stiffness was notable, as well as the safety factor, of course. The work was done at Logghe Stamping in Warren, MI. (The factory-supported Chaparral Camaros also had their cages done at Logghe.) The quality of the cage work was notable.

But we quickly discovered that building Camaros to the Trans-Am rule book was a monster task; everything was completely different in just about every way, which forced us to do everything from scratch and from our gut, basically. But that wasn't all, because as the workload increased, the stress on the crew increased exponentially. The first Trans Am race was held at Laguna Seca, in April, and it was clear that the team would not be ready, although Tony and Jerry went out to Laguna to show visibility for the upcoming OCF effort.

But there would be a seismic event upon their return that would alter the team forever. The OCF team's founding crew chief, Art Jerome, had been working incredible hours, as had the entire gang of OCF racing volunteers. At one point Tony suggested that Art go home and get some rest, and I'll let him describe what happened next: "The discussion degenerated into an argument and my Sicilian temper took over. The short story is that Art was gone from the team and would eventually surface at John Greenwood’s team, our arch enemy. That’s all I’ll say about that episode. We soldiered on." To say that this was a giant bowl of Not Good for the team was an understatement. This situation was about the abrupt cessation of loyalty and a calculated vindictiveness that was carried out against us over the next two years. And it wasn't pretty.

Needless to say, the team was shaken by the incident, but there was no time to dwell on it as the second race of the Trans-Am season, scheduled for Lime Rock, Connecticut, in May, was coming up fast. But remember when I mentioned that the political winds had turned against us at Chevrolet? And that our on-track success all of a sudden counted for nothing, especially since Jim Hall had been awarded the "factory" Camaro deal in Trans-Am? The following is a graphic example of the kind of bullshit we had to deal with.

We had been working on the front suspension modifications from drawings that Jerry had brought from Chevy, and from those Tony had the front springs wound at a local supplier. When we assembled the first car’s front and rear suspension and put the car on the shop floor to check ride height, the car’s front end was right on the deck. Uhh, WTF? The spring drawings - shockingly enough - must have been “wrong.” Come to find out that Chevrolet Engineering Center (CEC) had made special front spindles for the Chaparral Camaros that included mounting tabs for the Corvette J-56 heavy duty brakes. These parts were obviously crucial for the entire front suspension. When Tony inquired with his Chevrolet Engineering contact about obtaining some of the parts for our cars, he was told that "there are no extra parts available." Our entire program would be dead in the water without the special spindles.

We were incredulous, pissed-off, you name it. Tony called Jerry and said, essentially, WTF?, which was becoming the team's reluctant mantra at the time. Jerry called back a short time later and said that three skids (that's a lot of parts, folks) had just been shipped to Midland, Texas, for the "factory" Chaparral Camaro team. As Tony recalled: "I only called my dad (GM's Vice President in charge of Public Relations at the time) for help twice in my entire racing career. This was one of them. I told him the story and he made a call, to whom I’m not sure, but it was probably to a fellow GM VP. A short while later I received a call from my CEC parts contact and was told that the special front spindles were - shockingly enough - actually now available! So I ordered two car sets and a spare set (six pieces). And, oh by the way, they charged me $800.00 each!" From then on we knew what it was going to be like on the outside, looking in.

So what were we really getting into by deciding to compete in the 1970 Trans-Am series? After Mark Donohue had dominated the series in 1968 with his famous No. 6 Penske Racing Sunoco Camaro (one of my all-time favorite racing cars), humbling the Ford contingent along the way, okay humiliating the Ford contingent, and winning it again in 1969 (although Ford had stepped up their game considerably after Chevrolet had ruined the aero advantage of the '68 Camaro with the blunderbuss design of the '69), war was declared and there was an explosion in factory participation, with some of the best drivers in the world lined up by the factories to compete in the 1970 Trans-Am Series.

The atmosphere was electric even before the start of the 1970 Trans-Am season as Roger Penske, in a stunning move, had defected to American Motors to run the Javelin. It was a Hail Mary pass by the No. 4 Detroit manufacturer to gain visibility and get the Javelin nameplate in the discussion of desirable "pony" cars, and they had paid a steep price to get Penske (rumors suggested at the time that they had paid Penske more than double what his 1969 Trans-Am budget was). This was a jaw-dropping move in the racing world, believe me. So to counteract the loss of the famous racing team that delivered two consecutive Trans-Am Championships for Chevrolet, the aforementioned Jim Hall and his Chaparral Cars got the Chevrolet factory deal. Hall would be in the No. 1 Chaparral Camaro, while Ed Leslie would be in the No. 2 Chaparral team car.

The Owens/Corning Fiberglas Racing Team was given No. 3 for Tony's Camaro, and No. 4 for Jerry Thompson. A remarkable side note? As he did for the Owens/Corning Fiberglas Corvettes, GM design ace Randy Wittine would do his usual superb job laying out the paint design/graphics scheme for the OCF Camaros. The famous "speed blocks" were present and accounted for and the cars looked distinctive and very racy on the track in their red and white with black trim livery. (I almost got asphyxiated the day we painted the cars. I became disoriented in the fumes and started to pass out as I was painting the underside of one of the Camaros and had to be pulled out from under the car by Art Jerome and walked outside to get air. That incident could be filed under Not Good, to put it mildly.)

That said, take a long, hard look at that No. 3 on the side of Tony's car. As I mentioned in "The Glory Days, Part I", Randy Wittine would go on to become quite famous designing paint schemes and graphics for Roger Penske for many years and for many other teams in sports car racing, F1, Indy cars and yes, NASCAR as well. One of Randy's early clients beyond our OCF Racing Team and Penske Racing was none other than Richard Childress, of NASCAR fame. Yes, Randy's design for the "No. 3" that first appeared on the Tony DeLorenzo OCF Camaro in the 1970 Trans-Am season became the famous "No. 3" for Richard Childress Racing and Dale Earnhardt. Now you know.

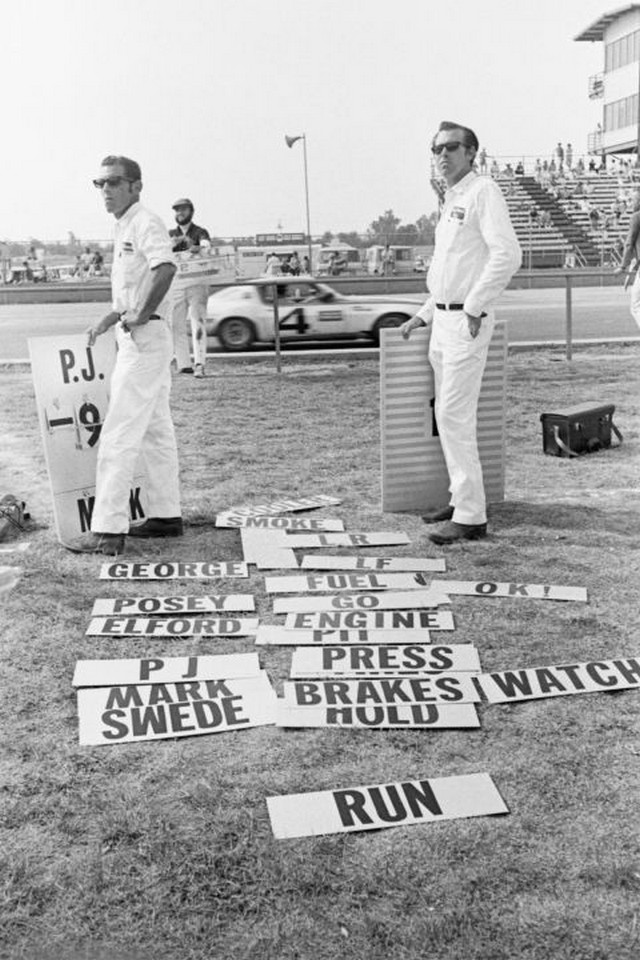

Mark Donohue would run his familiar No. 6 on his brand-new red, white and blue 1970 AMC Sunoco Javelin, and his teammate Peter Revson would be in the No. 9 Penske Racing team car. Other notables? None other than Parnelli Jones (No. 15 Bud Moore Engineering Ford Mustang Boss 302) would lead the Ford factory effort with "school bus yellow" Mustangs (he won the first race at Laguna Seca), and he would be joined by George Follmer in the No. 16 Bud Moore Engineering team car. The great Dan Gurney would field two, deep blue All American Racers-prepared Plymouth Barracudas, his traditional No. 48 would grace Gurney's machine (although he didn't run all of the races), while Swede Savage would join him in the No. 42 AAR team car. And Sam Posey (No. 77 Autodynamics Corp. Dodge Challenger) would carry the Dodge spear in the series with a bright green Challenger. The notable independents besides the OCF team were Milt Minter (No. 68 American Racing Associates, Inc. Camaro), Roy Woods (No. 69 American Racing Associates, Inc. Camaro), Warren Agor (No. 13 Camaro) and Mo Carter (No. 88 Camaro), all in '69-bodied cars.

Because of the OCF team's massive personnel uproar, and our new non-favored status with Chevrolet, we were up against it, big time. So we would only have one car ready for Lime Rock, which none of us was happy about, but given everything that had transpired, it was a minor miracle unto itself that we were able to show up. We arrived at Lime Rock after a 72-hour non-stop thrash with bloodshot eyes and still needing to finish the car. As anyone familiar with The Grind in racing can attest, when you start going uphill, things don't level out anytime soon. Had we bit off too much to chew? Possibly. But we were present and accounted for and we weren't shirking from the task at hand. The car, however, just wasn't right. It needed to be lighter and we needed more power, but given the circumstances it was the best we could do at the time. Tony's race ended with a head gasket failure after 22 laps. Parnelli won followed by Ed Leslie, Sam Posey, Jim Hall and the rest. Notable DNFs included Jerry Titus (Firebird), Donohue, Follmer, Revson and Savage. We didn't feel so bad about Tony's DNF after all.

The rest of the season went by in a blur. We got Jerry’s No. 4 OCF Camaro ready for the next race at Bryar Motorsports Park in Loudon, New Hampshire. It turned out to be one of the team's best efforts considering the caliber of the competition we were up against. We were racing against OEM Factory teams with some of the best drivers in the country and world. Follmer won with Revson second, Donohue third, Hall fifth. Jerry finished seventh and Tony was ninth. Ed Leslie was eleventh and Warren Agor’s Camaro came in twelfth. Again, there were notable DNFs, including Jones, Savage, Mo Carter (Tony's good friend in his privateer Camaro) Titus and Posey. And while the OCF team was fully engaged in the Trans Am wars, the team continued to kick ass in SCCA National races, as "The Streak" continued (see "The Glory Days, Part II").

Back to the Trans-Am. Next up was Mid-Ohio, and the team made a crucial error in car set up that cost us dearly. As Tony recalls: "I’m not sure why we had time to even consider it, but somebody said: 'That rubber vacuum line from the brake booster to the intake manifold sure is ugly. We ought to replace it with Aeroquip line and fittings.' Big mistake. While the Aeroquip steel braided line and aluminum fittings looked good, we had innocently removed the check valve that attached it to the power brake booster mounted to the firewall. The booster gave 'power' to the power brakes by drawing vacuum from the intake manifold on acceleration. Crewman, Cadillac Engineer and brake expert Fred Wood was not yet on the scene to watch this error unfold. The brakes would 'work' but extended full throttle runs would bleed vacuum from the booster. Simply put, application of the brake pedal would result in the pedal going to the floor. You had to pump the brake pedal to get the braking action you needed." All together now: Not Good.

Tony continued: "Transfer the above to going down the Mid-Ohio straight at full chat and then braking at the last possible moment to make the 90 degree right hand corner at the end. Jerry unfortunately drew the short straw and when he got to his brake point the pedal went to the floor, leaving him no room to avoid the woods at the end. The Camaro went into the woods and mowed down the biggest tree there. The impact 'cleaned off' the front end to the firewall. Miraculously, Jerry was not seriously hurt but he was hurting with severe aches and pains. We still didn’t figure out what we had done but I was wary enough to be pumping the brakes a lot in the morning practice on race day. The brake issue still bit me too but I was lucky enough to get the Camaro slowed enough at the end of the straight to avoid the woods but not the ditch at the end. The front end was damaged but not bad enough to put me out of the running."

Tony managed a tenth-place finish. Parnelli won followed by Follmer and Donohue. Mo Carter finished a tremendous fourth in his Camaro. Mo was a formidable competitor and he and Tony would become fast friends and do a lot of races together, including delivering a memorable overall win at the Pocono 500 IMSA race in 1973 in a brutally fast big block Camaro. Posey and Agor finished fifth and sixth respectively. We had a wrecked Camaro to rebuild but we were lucky that Jerry wasn’t seriously hurt.

The next stop, which was at Bridgehampton, among the rolling hills and dunes on Long Island, in New York, turned out to be a contentious weekend as the competitors were beginning to feel the pressure of the "win or else" mentality from their factories and corporate sponsors. There were even rumors of a fist fight after one of the drivers meetings. SCCA Chief Steward Berdie Martin admonished the competitors in no uncertain terms at the drivers' meetings, and John Timanus (the Trans-Am Series chief tech inspector) kept busy trying to keep the factories in line, which was a thankless task, as you might imagine. The tech inspections at each Trans-Am race were amazing examples of cajoling, whining and political gamesmanship on a grand scale, as factory representatives all pushed the rules to the limit to gain any advantage they could.

The OCF team showed up at Bridgehampton with the No. 3 Camaro only, as the No. 4 Camaro was still being rebuilt. Swede Savage captured the pole, but Donohue won the race. Follmer was second, Parnelli third, Hall fourth, and Carter fifth. Tony was a DNF with 59 laps completed. Another DNF followed for Tony at Donnybrooke, in Brainerd, Minnesota, as Jerry's No. 4 team car was still not ready.

Next up was Elkhart Lake's Road America, the beautiful 4.048-mile natural-terrain circuit cut out of the rolling hills of Kettle Moraine country in Wisconsin. And it was there that the ugly side of racing reared its head, as Jerry Titus was killed driving his Pontiac Firebird. As Tony recalls: "During practice we got an unwelcome lesson in what is always an unspoken possibility in motor racing – a fatal accident. Turn 13 is a fast uphill left hand corner that passed under a paddock access bridge at that time (the bridge has long since been removed). I saw the waving yellow caution flag as I approached turn 12, Canada Corner, and I slowed. I saw the Jerry Titus’ Firebird next to the outside bridge abutment with its front end heavily damaged. As I passed I could see Jerry sitting up in the car but he wasn’t moving that I could tell in the brief instant I saw him. Later the news came that he had succumbed to his injuries. It’s a sobering thing and we keep all drivers in our prayers." Qualifying was ruled by the factory Ford Mustangs of George and Parnelli. Leslie’s Chaparral Camaro was third; followed by Savage, Posey, Donohue, Revson, Hall, Minter, Agor, and Roy Woods. Tony qualified way back in twenty-first position and Jerry was dead last, with no time.

Mark Donahue rose to the occasion and won the race followed by Swede, Posey, Hall, Parnelli, Minter, Woods and Tony. The eighth-place finish would be Tony's best result in the 1970 Trans Am season. Considering the team's level of preparation - which was constantly in flux - and the fierce competition, it was as good as it was going to get. But we pressed on, and we never gave anything less than our best shot at all times.

Another DNF for Tony followed at St. Jovite, in Quebec, while Jerry brought the No. 4 OCF Camaro home in seventh place. Vic Elford won at Watkins Glen driving a Chaparral Camaro, Donohue was second and Follmer finished third, followed by Parnelli, Revson, Leslie and Carter. Tony finished ninth that day. After the race, Vic Elford stopped by our paddock spot and wanted to speak privately with Tony. He confided that they were running “angle plug” cylinder heads and would he vouch for their availability if/when John Timanus came over to ask about them? Well, well, well, politics is a bitch! Tony told Vic it was no problem. We had heard about the new heads but they were certainly not a “production” item yet by any stretch. Tony used his PR skills when John Timanus came by to discuss it with him. He told Timanus we had the new “production” cylinder heads but had not had time to put them on our engines yet. When we returned to Detroit there were, magically, three sets of the new "angle plug" cylinder heads waiting for us. Imagine that!

The next race was in the state of Washington at Seattle International Raceway in Kent, south of Seattle, in September. Parnelli won the race followed by Donohue and Posey. Tony and Jerry were both classified as DNF. The team limped to the final race of the 1970 Trans-Am season - at Riverside International Raceway southeast of Los Angeles - with tired engines and with no parts to refresh them. The outlook was bleak. Tony had engine trouble in the pre-race warm-up and Jerry was a DNF in the race. Parnelli Jones delivered a magnificent drive for the win and the Trans-Am Championship for himself and Ford. Follmer was second and Donohue finished third. They were followed by Savage, Gurney, Leslie, Minter, Woods and David Hobbs.

Our maiden foray into the Trans-Am Series was finished. It didn't go as well as we'd hoped, to put it mildly, but as Tony says, "I learned more about race driving that season than ever before. Surrounded by some of the best drivers in the world was a rare opportunity and well worth it."

The team regrouped to post its triumphant result at the Daytona 24 Hours the following February, but we would never race those Camaros again. And even though the Owens/Corning Fiberglas support was over, we - as a team - were not finished. The '71 Trans-Am season would be an entirely different story altogether, having seen the writing on the wall and tired of playing games with the powers that be at Chevrolet, we would buy two of those ex-factory Ford Mustangs from Bud Moore for the '71 Trans-Am Season.

And we haven't even gotten to the story about our infamous Budd-sponsored "super" Corvette yet.

Stay tuned.

(The DeLorenzo Collection)

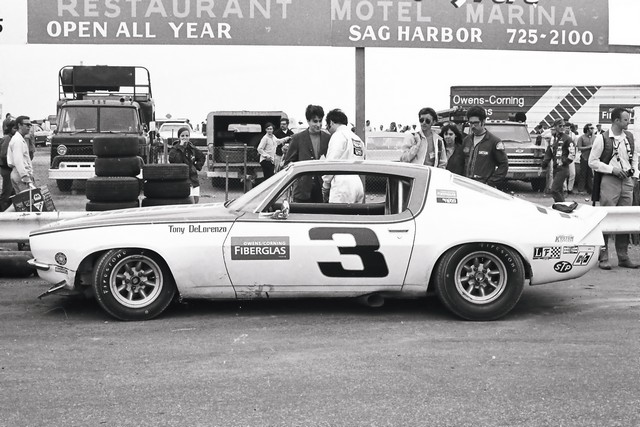

The Owens/Corning Fiberglas Corvette Racing Team debuted one of its new Trans-Am Camaros at the second race of the 1970 Trans-Am season at Lime Rock, Connecticut. It was another monumental thrash for the team to get ready for that race weekend, and a frustrating result too. Tony would suffer a DNF after 22 laps due to a blown head gasket. The car gleamed in its new Randy Wittine-designed OCF livery.

(The DeLorenzo Collection)

A closer look at the famous "No. 3" design by Randy Wittine on the side of Tony's car at Lime Rock. Randy would go on to become quite famous designing paint schemes and graphics for Roger Penske for many years and for many other teams in sports car racing, F1, Indy cars and yes, NASCAR as well. One of Randy's early clients beyond our OCF Racing Team and Penske Racing was none other than Richard Childress, of NASCAR fame. When it came time for Randy to work up a graphics package for Richard in NASCAR, Randy used his original design for the number "3" that had first appeared on Tony's OCF Camaro in the 1970 Trans-Am season. Yes, it became the famous "No. 3" for Richard Childress Racing and Dale Earnhardt. Now you know.

(The DeLorenzo Collection)

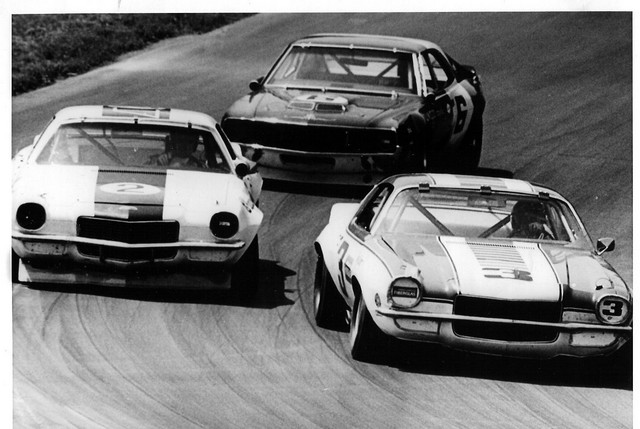

Tony DeLorenzo (No. 3 Owens/Corning Fiberglas Camaro), Ed Leslie (No. 2 Chaparral Cars Camaro) and Mark Donohue (No. 6 Penske Racing Sunoco Javelin) at the Mid-Ohio Trans-Am in 1970.

(The DeLorenzo Collection)

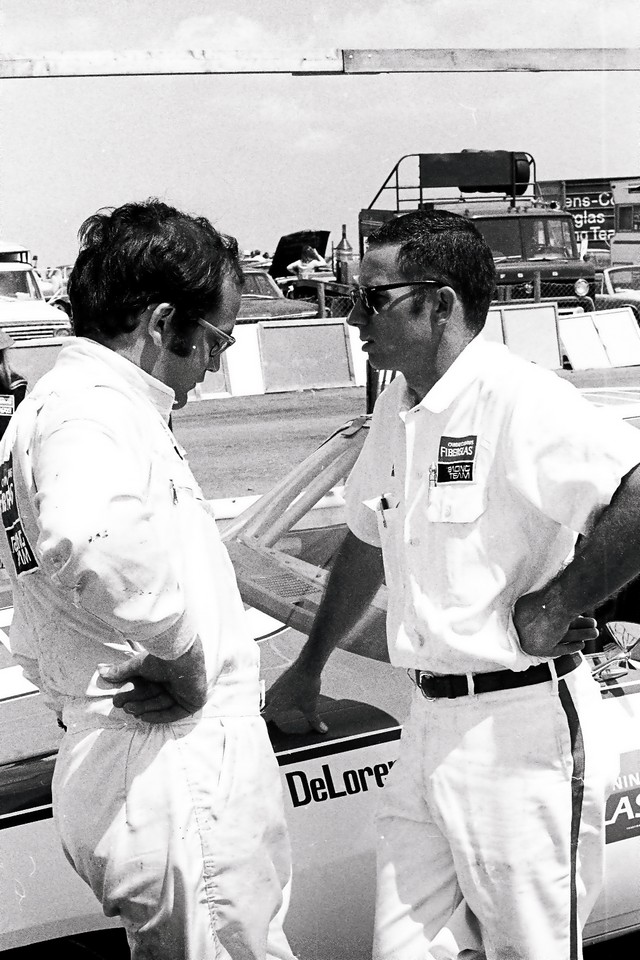

The Trans-Am race at Bridgehampton, among the rolling hills and dunes on Long Island, in late June in New York, turned out to be a contentious weekend as the competitors were beginning to feel the pressure of the "win or else" mentality from their factory overlords and corporate sponsors. There were even rumors of a fist fight after one of the drivers meetings. Here SCCA Chief Steward Berdie Martin (with back to camera) admonishesthe competitors in no uncertain terms at one of the drivers' meetings that weekend about on-track behavior.

(Photo by Roger Holliday/The DeLorenzo Collection)

Crewman Harry Lambert (right front of car) at the weigh-in of the No. 3 Camaro at Bridgehampton, with Blaine Ferguson visible behind Harry (Blaine was another OCF team member who went on to work for Penske Racing). Rollie Aiken is at the left rear of the car, while Tony stands by the driver's door. John Timanus, the Chief Technical Inspector for the Trans-Am Series, was kept extremely busy trying to keep the factories in line, which was a thankless task as you might imagine. The tech inspections at each Trans-Am race were amazing examples of cajoling, whining and political gamesmanship on a grand scale, as factory representatives and crew chiefs all pushed the rules to the limit to gain any advantage they could.

(Photo by Roger Holliday/The DeLorenzo Collection)

Tony DeLorenzo and Crew Chief Rollie Aiken stand by the No. 3 OCF Camaro, pre-race at the Bridgehampton Trans-Am.

(Photo by Roger Holliday/The DeLorenzo Collection)

Tony at speed at Bridgehampton. Another DNF, this time after 59 laps.

(Photo by Roger Holliday/The DeLorenzo Collection)

The No. 3 OCF Camaro in the pits at Bridgehampton. Note the clean graphics and the "No. 3"; the Minilite racing wheels (the hot setup back in the day) and the OCF transporter in the background. And the scars are evident from the Trans-Am "wars" too.

(Photo by Roger Holliday/The DeLorenzo Collection)

The Bud Moore Engineering pit crew is in the foreground as Jerry Thompson (No. 4 Owens/Corning Fiberglas Camaro) speeds by in the background at Riverside International Raceway in 1970. It was the last appearance for the OCF Camaros.

(The Petersen Automotive Museum)

(The Petersen Automotive Museum)

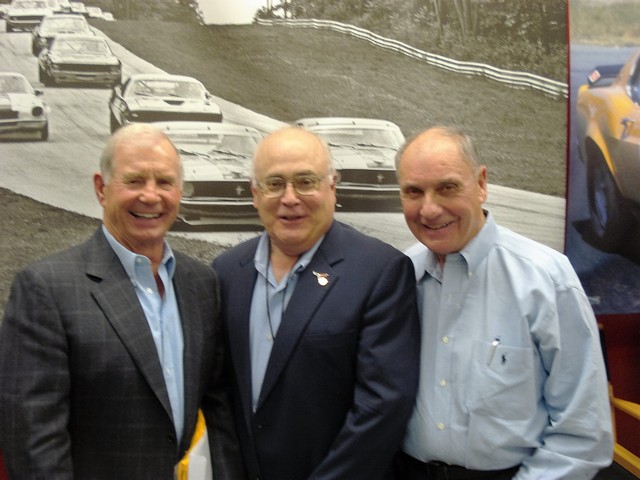

Parnelli Jones, Tony DeLorenzo and George Follmer at a special Trans-Am reunion event at The Petersen Automotive Museum, November 2009, in Los Angeles.