Editor's Note: Peter is taking a summer break from writing "Fumes" although he will write a new column if news from the sport dictates as such, and we will continue our weekly racing updates in "The Line," this week featuring IndyCar from Pocono, NASCAR in Bristol and the new Penske Acura entry in the 2018 IMSA WeatherTech SportsCar Championship. But as a bonus, we're continuing to re-run Peter's riveting series, "The Glory Days," in its entirety. The inside story of Tony DeLorenzo's racing career (Peter's brother), one of the most successful Corvette racers of all time - including the fantastic exploits of the famous Owens/Corning Fiberglas Racing Team - was one of the most widely read and popular pieces ever to appear in Autoextremist.com. This week, in Part VI, Peter recounts a time of transition as the Owens/Corning Fiberglas relationship comes to an end; acquiring two Bud Moore factory Ford Mustangs for the '71 Trans-Am season after Chevrolet operatives deemed us as being "expendable" and the creation of the infamous "Monster" Corvette. So enjoy, because it was a different time and a different era, one never to be repeated. -WG

By Peter M. DeLorenzo

© 2017 Autoextremist.com

Detroit. If you’ve been following along in the previous segments of “The Glory Days” (Parts I, II, III, IV and V; Scroll to the bottom and click on "Next 1 Entries" to read previous columns -WG), we’ve given you a front-row seat to my brother Tony’s racing career and the incredibly successful run of the Owens/Corning Fiberglas Corvette Racing Team. From late summer in 1968 through to the win in the 1971 Daytona 24 Hour race, it was the most successful Corvette team in both SCCA “A Production” racing and FIA GT endurance racing here in the U.S.

But after running the Corvettes again and additionally hammering around in the 1970 Trans-Am Series in our OCF Camaros without factory help, the ’71 Daytona 24 hour race marked the end of the relationship with the Toledo, Ohio-based Owens/Corning Fiberglas corporation. I delineated the reasons in last week’s column, but suffice to say the 1971-72 racing seasons would mark a huge transition for us.

Before the team’s final triumph at Daytona in February of ’71, the previous summer had been a painful lesson in racing politics. We found out that restoring the Corvette name to prominence on America’s racetracks counted for absolutely nothing with certain powers that be within Chevrolet. It didn’t sit well with us, at all. And Tony was determined to make some changes. Tony formed Troy Promotions, Inc., which would now be the official entrant whenever we showed up at a racetrack. And after the bitter experience with Chevrolet racing politics in the ’70 Trans-Am Series, Tony decided to make an emphatic statement as to what he thought about the experience. He pitched a local businessman successfully, which allowed us to buy two factory-prepared Ford Mustangs from Bud Moore Engineering, the same cars that we had run against in the 1970 season.

I’ll never forget that day in March when we unloaded those two Mustangs into our shop after the trip from Spartanburg, South Carolina, and found out just how “non-stock” they were. After crawling all over and under them, we discovered that these were two, highly-modified Mustangs that bristled with factory tricks and some old-fashioned stock car secrets from Bud Moore. They may have been in the “spirit” of the Trans-Am rules, but don’t kid yourself, these were radically reinvented Mustangs that won the 1970 Trans-Am Championship for a reason.

Not long after we acquired the Bud Moore Mustangs, the phone rang at the shop and the voice on the other end of the line introduced himself to Tony and said, “You need me.” Tony said, “I do?” The voice belonged to accomplished race engineer Mitch Marchi and he said, “Yes you do.” A meeting was set up to discuss what Mitch could do for us, and it proved to be fortuitous. Educated at GM Institute (GMI), now Kettering University, in Flint, Michigan, Mitch spent a brief stint at Chevrolet Engineering in Warren, Michigan. When he found out that Ford was hiring racecar engineers, off he went. He spent many years at Ford, with the most exciting work being his stint at Ford’s Kar Kraft operation doing engineering on the Ford Mark IV. He also worked on a Land Speed Record car, other go fast projects and the Trans-Am Mustang racing program. Mitch would use his valuable experience in chassis design, fabrication, and race craft to improve the performance of our racing cars. Needless to say, we would not have had the success we had during the 1971 Trans-Am season and beyond without Mitch’s help.

The 1971 Trans-Am season would be different in that there would only be two factory-supported teams as opposed to the four that competed in 1970. Roger Penske returned with the new-look ’71 AMC Sunoco Javelin, which would be driven again by Mark Donohue. And Bud Moore Engineering would be back with two factory-supported Ford Mustangs driven by Parnelli Jones (for one race only) and George Follmer and Peter Gregg.

After doing our usual pre-race thrash over several days, Tony and I headed out to the opener for the ’71 Trans-Am Series at Lime Rock with our new trailer, which was newly-acquired from Dan Gurney’s All-American Racers and painted in the new-look Troy Promotions colors of black, white and blue. Randy Wittine had performed his usual magic and our new Mustangs and the transporter looked fantastic.

As anyone in racing will tell you, mental and physical exhaustion plays an integral role in the sport. It’s just the way it is. I had fallen asleep in the cab somewhere on the Ohio Turnpike, while Tony was at the wheel. I woke up suddenly to discover that Tony was fast asleep, and the whole rig was heading toward the median, at a severe angle. After I yelled loudly, Tony woke up, straightened the rig out just in time, and we stopped at the next rest area for some coffee. Ah, racing stories, we got a million of ‘em.

Lime Rock was a real eye-opener, for a number of reasons. First of all, the weather forecast for the weekend wasn’t good. It was supposed to rain all weekend with even heavier rain on race day. And it took us all of about five minutes to discover that our Firestone rain tires were no match for Goodyear’s brand-new racing rain tires, as in seconds a lap slower, which in racing is an eternity.

We secured a set of Goodyear rain tires for the race, and the promised deluge appeared right on cue. Jerry Thompson went off coming out of Turn 1 in the early going and promptly got stuck in the mud in the No. 4 TPI Mustang, with Tony going on to finish second to Mark in the No. 3 car. Donohue spanked everybody that day running like a freight train lap after lap.

And it was at Lime Rock that I learned a valuable lesson about Roger Penske. We had arrived at Lime Rock prepared, but barely ready, if you know what I mean. And the rain added chaos to the mix. I remember standing in the pit lane, soaked through to the bone in my T-shirt and jeans, handling pit signals for Tony during the race. I looked down the pit lane and there was Roger, cool, calm, collected – and bone dry - in a head-to-toe rain suit complete with a hood. It was right then and there that I learned that Roger is always prepared, and it’s easy to see why he remains the most successful racing team owner in history to this day.

We ran nine races in the TPI Mustangs that season, with Tony recording a second, third and fourth for a very solid effort, but not good enough when winning is the name of the game. Another lesson learned? We had contracted with Bud Moore to build our engines for the season, but after Tony and Jerry ran very strong in the first few races, Tony said that the engines were all of a sudden not as good. We started doing our own engine rebuilds about halfway through the season. Oh well, onward.

Though the 1971 Trans-Am season provided a measure of redemption for Tony and the team after being marginalized by Chevrolet in 1970, 1972 would be the toughest year. With no sponsors on the horizon, Tony and Jerry ran the “Daytona 6-Hour” (the race had been shortened due to the energy crisis) with Ron Weaver in a Corvette co-owned by Weaver and Steve Mair (son of Alex Mair, Chief Engineer at Chevrolet at the time). Thanks to troubles with the experimental radial construction racing tires that the team had agreed to run, the Corvette was a DNF in the first hour of the race with Jerry at the wheel.

With the 1972 12 Hours of Sebring coming up, the team decided to enter one of its TPI Trans-Am Mustangs in the race with partial sponsorship from Marathon Oil. We were part of a four-car effort sponsored by Marathon, which included two Chevron B19 machines and a Ferrari 365 GTB4 Daytona driven by David Hobbs and Skip Scott. Our plan was to win the over 2.5-liter Touring Class (TO) and finish as high overall in the race as possible. The idea was that the PR value for our win would help us land sponsors for an all-new Corvette effort planned for IMSA/FIA races in 1973.

Tony and Jerry planned with Crew Chief Deryl Denman to run a conservative, 6,000 rpm rev limit while using the tires and brakes like it was a sprint race. In the course of the ‘71 Trans-Am season we had learned to change two tires and add fuel in sixteen seconds, so it seemed like a good plan. And the strategy worked beautifully - with Tony and Jerry running sixth overall and second in class in the early hours of the race – right up until the point when the team discovered that the ride height was set too low and the rough Sebring track had pounded the oil pan into submission, running all of the oil out of the engine. File that one under the best-laid plans… The 1972 12 Hours of Sebring would mark the last time that Tony and Jerry would team up in a racing car.

The rest of the 1972 racing season for Tony was marked by a few guest drives, including one in a Ferrari 365 GTB/4 at the Watkins Glen 6-Hour race. But there was one memorable event in particular, an IMSA road race that was run on the Talladega Superspeedway infield road course the day before that summer's Talladega 500 NASCAR race. Tony would run a all-aluminum big-block Corvette entered by his old friend Bill Morrison in a race where the IMSA cars were combined with NASCAR’s Grand American series for "pony cars" led by none other than Tiny Lund. Even though the Grand-Am cars would start first in a split field of cars, Tony and Bill would move into the lead of the race handily, kicking everyone’s ass. But then a valve seat disintegrated with five laps to go, and Tony and Bill had to settle for second place. Ironically enough, the winner that day was Tony’s now late friend Dr. Wilbur Pickett, who was driving an ex-Owens/Corning Corvette that had been purchased by team owner Bobby Rinzler. But another important lesson was learned that weekend that would play into the building of “The Monster” – the Budd-sponsored 1973 Corvette.

Tony envisioned an all-new Corvette that would incorporate the countless lessons learned in running the championship-winning Owens/Corning Corvettes, plus new thinking from some of the most creative engineering minds in the business. This “Monster” Corvette would be the culmination of everything we knew. Mitch Marchi would team with Lee Dykstra (the famous racing car designer and fellow ex-Kar Kraft engineer) to design this all-new Corvette racing machine for Troy Promotions. At the time it would become the most sophisticated (and fastest) Corvette in the IMSA series. Here’s how it came about.

First things first, we needed a sponsor. One of Tony’s proposals landed on the desk of Jose DePedroso at the Budd Company in Detroit, a maker of automotive body and chassis components for the major auto manufacturers. He was an unabashed racing fan and thought the sponsorship of a Corvette racing car could help promote Budd products to their OEM automotive customers. Tony then sold the idea up the ladder to Gil Richards, the Budd CEO, and we had a program. Armed with the first full sponsor since the OCF days, we had five months to design and build a world-beating FIA Corvette racing car for the first race of the season, the 1973 Daytona 24 Hour, which was coming up fast in February.

Crew chief Deryl Denman, who had worked at Cadillac engineering and was then working for Borg-Warner, had gathered a brain trust of his former mates at Cadillac engineering. Most had worked on the OCF cars, but some were new to the group. Fred Wood was a chassis development engineer working at the GM Milford Proving Ground. Rick Cronin and Bill Boskey were working in service engineering in Detroit. Ken Wiedbush worked in manufacturing engineering, also in Detroit, and was one of our electrical gurus. Les Talcott worked at Chevrolet Engineering and was an electrical and engine specialist, and the aforementioned GM Design legend Randy Wittine, who had been with us since 1967, would develop the paint scheme for the Budd Corvette. There were also a limitless supply of engineers and engineering students clamoring to help for free (they only got travel expenses if they were actually part of the crew that went to the races).

There were others, including Bill King, whose engine shop was down the street from our Troy Promotions shop, and A. I. LeGrand Wood III, “Woody” as we knew him. Woody was an engine expert, painter, and all around character. Despite the political upheaval aimed at us by certain bureaucrats at Chevrolet, we had maintained close contact with Gib Hufstader at Corvette Chassis Development. He was an inexhaustible source of the latest goings on with the Corvette heavy-duty parts development activities. Gib also drove for the OCF team at Sebring in 1969. Gib also let Zora Duntov, the legendary Corvette Chief Engineer and Father of the Corvette, know what we were doing and kept him advised of our progress with the all-new “Monster” Corvette.

The first two scheduled races in 1973 were 24 (Daytona) and 12 hours (Sebring) long respectively, and the rest of the season’s IMSA races were usually 250 or 500 miles. We needed to rethink our approach to car building, and Mitch Marchi and Lee Dykstra were the ones who would do the design work and drawings to make that happen. Deryl and the crew would work on the powertrain and electrical systems to apply what we had learned the hard way in the last three years. They would be responsible for the entire project, making sure everything came together as planned.

We contracted Bill King to build and dyno two over-bored 454-cubic-inch big block Chevy engines for Daytona. The final displacement for Daytona worked out to be 467 cubic inches. It was significant that we were getting away from the 427 cu. in. L88 engines that had served us so well in the OCF Corvettes, but Tony had learned while driving Bill Morrison’s Corvette at Talladega the previous August that the 427 was no match for the 454 “long stroke” motor. Bill and Woody were working on our “mini” (as in low budget) engine development program down the street from our shop.

The rest of the power train would be built by our long time axle and transmission man, Ehrling “Spike” Olilla. Spike worked at Chevrolet engineering in the axle build room, so we always had the latest parts and assembly modifications in our axles and transmissions. Spike worked out of his garage at home in Warren, Michigan. A gruff, tough, but friendly man, Spike had crewed on the OCF cars when we won the GT class and finished sixth overall at the 1970 Daytona 24-Hour, with Jerry Thompson and John Mahler driving.

Spike’s two sons, Nick and Mark, also worked for us on the OCF Corvettes and Camaros before they went off to work for Roger Penske and Mark Donahue. Nick stayed with Penske Racing for most of his career and did extremely well, eventually winding up running their NASCAR engine operations. Troy Promotions was referred to as the “Training School” by Mark Donahue, and at one time at least five Troy Promotions alumni worked for Penske Racing. We joked about it a lot.

Meanwhile, back at the shop, Tony and Deryl were going though parts lists and bugging the parts manager at Bill Wink Chevrolet in Dearborn to get what we needed in time to make our schedule. One of the major items was a new frame, which would be heavily modified and reinforced prior to the body getting bolted on and the construction of the roll cage completed. The other crucial component was a body. We had ordered a body from GM service parts when we built the L88 Corvette to make the 1968 Daytona 24-Hour as part of the Sunray DX Corvette team, but we didn’t think we had enough time to do it that way again. We had located a Corvette roadster body in Wisconsin, just north of Deryl’s family farm near Antioch, Illinois. All we had to do was go over there and get it.

Tony and Deryl hitched the trailer to the TPI Chevy pickup and headed west (but not before making a memorable overnight stop to visit Bill Morrison and friends in Chicago along the way). They located the farmer/drag racer who was selling the Corvette body and, after determining that it was suitable for our purpose, paid the money, loaded it on the trailer and headed back to Detroit. Once back at the shop, we set about prepping the frame with reinforcements and re-welding critical areas.

Mitch had sketched drawings for the roll cage and we attached the body to the completed and freshly painted frame. Randy Wittine visited the shop for a couple of nights, attaching the fender flares to the body. We sent the body/frame assembly to Tom Smith at Wolverine Chassis in Romulus, Michigan. Tom was an accomplished car builder, specializing in Pro Stock drag cars, and he fabricated the roll cage and some of the chassis and interior pieces as well. The finished product was beautiful.

While all this was going on, Mitch and Lee were producing a blizzard of drawings for the chassis parts. Nothing was left to chance as all the rubber bushings in the car were replaced by solid bushings or spherical bearings. A-arm cross shafts were machined from solid billet; new sway bars were fabricated by a local shop; and many other chassis parts were fabricated out of stronger stock for greater stiffness and precision. Chassis geometry was also changing while we were at it. The Budd Corvette was going to handle like no other Corvette before it.

The front and rear hubs were re-machined for zero run out, as were the front and rear spindles. All the parts were x-rayed and shot-peened in critical areas. Boltholes for wheel studs were expanded to ½ inch and trued for radius. We had the wheel studs manufactured out of high strength steel alloy, with rolled threads and pilots so the lug nuts would seat while being driven with an impact wrench set at 200psi. We had a groove machined on the nose of the heat treated lug nuts that would capture the inside diameter of a plastic plug, the outside diameter of which would snap onto the steel bushings that were inserted into the Minilite magnesium wheels. It was a simple, clean way of retaining lug nuts on the wheels when making pit stops. We had used them on our Trans-Am Mustangs during the 1971 season while others were gluing lug nuts onto their wheels. (Our pit stops that year equaled the speed of Penske Racing.) We also had a selection of special rate springs wound for the front and new leaf springs made for the rear suspension. Most of this “new” technology had been in use in our Trans-Am Mustangs, compliments of Mitch and Lee.

Our work tempo increased as time began to be an issue. Fred Wood worked on the brakes. The IMSA rules allowed us to improve the braking system, and improve we did. The decision was made to use Lincoln calipers similar to the ones used on the Mustangs we raced in the Trans-Am. We had quick change spring loaded brackets instead of cotter pins to retain the brake pads, as well as a vacuum retraction system on the master cylinder. We had used the vacuum retraction system on the OCF Corvettes for the long distance races. Fred worked out all the calculations for master cylinder and push-rod size and all the other details needed to have a bullet proof braking system. After years of struggling with marginal brakes, we knew things would be a lot better in the new car. And the Budd Company would supply us with special curved vane Corvette brake discs to aid cooling.

Anybody familiar with building race cars knows that the devil is in the details, and where the car’s systems are concerned, there are myriad details. We needed an electrical system that would give no trouble over the long hours of an around the clock race. We had won the GT class and finished fourth overall in the 1971 Daytona 24-Hour, but we had fought a running battle with the electrical system. We didn't want a repeat of that. To solve the alternator problem, Bill Boskey and Ken Wiedbush came up with a heavy-duty Delco 125 amp alternator that would handle the increased loads. They designed a cog belt and pulley accessory drive system that would run trouble free for a lot longer than 24 hours. Modern circuit breaker panels were designed, replacing glass fuses, and, for some time, we had already been using a switch to change ignition modules in an emergency instead of manually plugging in the new one. We were way ahead of our competition on that item, thanks to Les Talcott.

We found an aircraft battery supplier, in Marathon. They agreed to provide us with very lightweight batteries (8lbs.) that would crank the 467 cu. in. V8, with no trouble. We couldn’t believe how well the batteries performed and they never gave us any trouble. We also found Highland Bolt and Nut in Highland Park, Michigan. The company provided TPI with an unlimited supply of grade 8 fasteners, essential ingredients for a proper racing program.

Meanwhile, crew chief Deryl Denman was working on an oil cooler system for the transmission and rear axle. The OCF cars had been using twin marine bilge pumps with high-temperature-resistant impellers. That system worked but it was a high maintenance item and we had begun to experience some impeller failures. Using a Lincoln electric motor to drive a small aluminum reduction gearbox, chain coupled to two heavy duty cooking grease pumps equipped with Teflon® impellers, Deryl attached the entire system to a T-shaped aluminum plate. Ignoring derisive cries of “mad-scientist” and other endearing terms from the crew, Deryl soldiered on, determined to demonstrate the system’s durability. He mounted the plate on a five-gallon bucket of 90-weight gear lube and plumbed it to act like the closed system with the two oil coolers in the race car. Every day, all day, at the shop he would run the system hooked up to a DC power source. Other than the faint stench of green gear lube, the system built up three weeks of running time without a hiccup. We were forced to bow to superior engineering power, and somebody who was adept at surfing though the industrial products catalog But that is what good engineers do, and Deryl was definitely one of those.

But the biggest task was shoe horning the lube pump system, two oil coolers, the ducted fresh air blower system, the Marathon battery, and the 22-pound Halon fire-suppression bottle into the rear compartment of the race car. The system also fed cooling air to the rear brakes. We reasoned that 200°+ air from the oil coolers would cool the 1000° rear brakes. Somehow the crew got it all to fit and everything worked as advertised, including the fire suppression system, which would come in handy two years later during an ill-advised street race in Pontiac, Michigan. (More on that in another chapter.)

The team agonized over how to run the engine since they were using the long stroke motor for the first time. Since Bill King’s dyno runs were showing the 467 to be a torque monster, we reasoned that we could run the engine at a lower rpm and use a “longer” gear. We had been using a 2.73:1 gear ratio at Daytona for four years. We discussed our plans with Gib Hufstader at the Corvette Chassis Group. He said that Chevrolet had produced a few special 2.42:1 ring-and-pinion sets for some Corvette Bonneville racers, and he agreed to have one of the racers ship the parts back to Detroit so we could use them for Daytona. Spike built the 2.42 axle, and we would use a 2.73 for a spare. So we made the preliminary decision to run the engine at 5,500 rpm in the lower gears and let it run to whatever it would pull on the straight; 200+ mph was our goal, along with “bullet proof” reliability. (This would prove to be a fateful decision later.)

In typical racer fashion, final assembly of the Budd Corvette began to demand ever longer hours as time grew shorter. The drive train, plumbing, electrical, and safety systems all went forward, but the inevitable details would keep the team busy right up to the planned departure date.

Tony and Deryl had been reading and re-reading the IMSA and FIA rules for the 24 Hour. IMSA was sanctioning the race and there was a section in the rulebook on exhaust systems and the collector length. The rule, for front engine cars, was that the collector had to go at least to half the length of the wheelbase, exiting toward the rear of the car. Up to this time, most Corvettes would end the exhaust just in front of the rear wheel. The dyno runs had indicated that “short” was the way to go. Installed, the short exhaust collectors were startling in appearance to all of us, and, as it would turn out, to our competition also.

The race date was Saturday, February 3, 1973. Practice started on Thursday, February 1, so we wanted to be there on Tuesday night so we would have time to get set up for practice and the race on Wednesday. This would mean that we would have to leave no later than Monday night for the nineteen-hour tow to Daytona.

Tony asked Mo Carter, legendary racer and Chevrolet dealer from Hamilton, Ontario, to be his co-driver in the Budd Corvette. Mo was very fast and good with the equipment. He was also used to big, high-powered cars since he drove his own Camaros very successfully.

We had ordered a Chevy van from Wink Chevrolet (Bill Wink III was a grade-school and high-school classmate of mine) for a tow vehicle, and it was overdue from the factory in Union City, Indiana. We’re talking a “bread van,” a medium-duty truck powered by a 454 engine, not the van you see in the church parking lot. But, there was an issue. It seems that the new truck had suffered a blown engine in Bowling Green, Ohio, while being driven from the factory to Detroit, while it was towing a second truck. There was no time to refit the truck with a new engine, which would mean that we would have to rent a truck big enough to haul the team’s considerable amount of “stuff” to Daytona. It’s always something in racing.

Besides the crew and Mo Carter, Lee Dykstra would make the trip representing Mitch and their engineering efforts. Fred McKenna would be flying in from St. Louis. Fred worked for Lampert Firestone and would be handling our tires for the weekend. The OCF team had used Lampert the previous five years, and they were good friends. Last, but not least, was our “crack” PR man Chuck Koch who was coming in from L.A. Chuck and Tony had met several years earlier when he interviewed Tony for articles he did on the OCF Corvettes. Chuck was ably taking over for Roger Holliday from Owens-Corning.

Word of our Budd Corvette project had even reached the executive level at GM, and Tony got a call from Bill Mitchell, VP of GM Styling (now Design). My father had introduced us to Bill and we had seen him regularly, since he lived only a block from our house. He was enthused about the effort and asked Tony if there was anything he could do to help us out. Tony thought about it for a moment and then asked if Bill could arrange for us to get one of the heavy, padded car covers GM Styling used when they towed cars from the GM Tech Center to the Milford Proving Grounds. Bill made sure we had a specially-fitted Corvette cover in time to use it on the trip to Daytona.

We were getting into the third week of January and our workdays were getting to be 16–18 hours long. It became clear that we were going to have to leave some minor things for finishing in the garage at Daytona, including final suspension settings and electrical checks. The engine was ready to go because it had been run in and hot-torqued on Bill King’s dyno, but we were still working on the fuel system and a number of other things as time began to run out.

A huge item missing from the equation? Getting the car painted. Spike’s neighbor across the street was Jerry Pennington, owner of Pennington Collision in Troy, MI. We had known Jerry for a number of years and his work was always flawless. Jerry was a regular entrant in the annual Autorama, Detroit's Hot Rod Show. His custom car creations had won numerous trophies there and at car shows around the country.

Tony called Jerry about getting the car painted and they talked about timing. When Tony told him that we couldn’t get him the car until Saturday morning, the weekend before we had to leave, Jerry smiled and allowed as to how it would be “close.” He also told Tony that there was no time to get a super job done, but he knew we were desperate. Randy Wittine helped out with surfacing and laid out the striking white, blue, and black color scheme. We’re pretty sure Jerry, Randy and the Pennington guys worked around the clock that weekend.

The team picked up the Corvette on Monday morning from Pennington’s. There had been no time to put clear lacquer on the car, but it still looked beautiful to us. Photos of the car at the track confirm that the paint job was excellent. (Jerry would redo the paint for the upcoming Sebring race to include the clear coat.)

Monday morning? That’s right, our departure time was blown and we grimly began loading the truck while Deryl and the guys tried to get more work done on the car. We had to take “everything” in the shop to be able to change anything on the car that might break in addition to all the pit equipment, spares, fasteners, tools, and related items. We worked late into Monday night, finally declaring the truck loaded and the car done as much as it was going to get done in the shop. The list of “things we’ll do at the track” had gotten a lot longer.

Several of the team members had worked nearly 24 hours a day for the last week and exhaustion was setting in, but that’s racing. Early on Tuesday morning the Troy Promotions vehicle fleet consisting of a rental truck and trailer carrying the Budd Corvette (no big trailer rig this time), the TPI pickup, Bill Boskey’s Cadillac Fleetwood engineering vehicle and an assortment of other vehicles pulled out of the shop and headed for Daytona. Tony didn’t remember who was driving what when he got into the back seat of the Fleetwood and collapsed. I’ll let him describe it: “I do remember waking up and asking where we were. ‘Chattanooga’ came the reply from the front seat. I realized that the definition of exhaustion was sleeping in the back seat of a Cadillac Fleetwood for 700 miles without waking up.”

The team arrived in Daytona Beach at 3:00 a.m. on Wednesday morning and managed to grab a few hours sleep at the hotel before going to the Speedway. There was a lot of work to do on the car before presenting it for tech. A front spoiler needed to be fabricated and the closeout for the fuel filler on the rear deck needed to be addressed, among many other smaller projects.

Chuck Koch recalls his arrival at the track on Wednesday morning: “My roommate was Lee Dykstra, and he arrived Tuesday evening. We got to the track the next day and found you guys weren’t there yet, so we stood around in the assigned garage area and waited. Sometime later Tony finally showed up looking a bit harried with a half-built racecar on the trailer, and the crew set about finishing the car. At one point Zora Duntov made a surreptitious appearance (as he had to in those days since GM wasn’t in racing, you know), and surveyed the scene with a certain amount of concern in his eyes (perhaps he was reliving 1957 Sebring when the SS Corvette was pretty much completed at the track while practice was in session). Tony and Zora huddled together in the corner for a while, making important-looking hand gestures and sharing the occasional pensive look at the crew’s work. I always wanted to know what was said.” Tony had this to say: “I can’t remember what Zora and I talked about, but I’m sure it was really important.”

The team got Mo Carter fitted to the seat and the car was presented for tech inspection. There were no issues, although there was a brief discussion about the short exhaust collectors, but the rules were consulted and we were deemed race worthy. It helped, of course, that the sanctioning body was IMSA, if it were the SCCA it might have been a different story.

While the tech inspection prep was going on, other crew members were busy setting up the pit space for the long race. That consisted of setting up lights, a generator, timing benches, an inventory of spare parts, tools, and all the items needed to perform routine pit stops, as well as the emergencies we knew we might have during the long night of the race. Practice would start the next morning.

So, here we were. We had struggled mightily to get the Budd Corvette ready against all odds, and now we had to do battle with the toughest competitors in the business, some of who used to be on our side. No quarter would be asked; none would be given. We would do our best to avoid a mistake, and we hoped to make our own luck.

There were four classes at the 1973 Daytona 24 Hour: Sports 3000 (3-liter); Sports 2000 (2-liter); Grand Touring +2000 (big engine GT cars); Touring 5000 (5-liter sedans); and Touring 2000 (2-liter sedans).

The Budd Corvette was in the Grand Touring +2000 class along with 24 other cars. Most of these were Corvettes, but Luigi Chinetti, Jr. was there with his N.A.R.T. (North American Racing Team). They brought four Ferrari 365 GTB/4 machines, one of which was being driven by Milt Minter, Tony’s old friend from the Trans-Am series.

The other Corvettes entered were being driven by a gallery of competitors that we knew very well. Jerry Thompson was driving with Mike Murray and Ike Knupp in the Murray Racing Corvette. Don Yenko, one of Tony’s co-drivers at the ’71 24 Hour, was driving for arch rival John Greenwood's team, along with Jim Greendyke and Bob (Robert R.) Johnson. Greenwood would be driving with Ron Grable in his other Greenwood team car. Dave Heinz was sharing his Corvette with Bob McClure and Dana English. This group of drivers had all spent the last five years racing with and against each other, and they all had the same thing on their minds: win the race and let everybody else fight over the scraps.

The next biggest class was Touring 5000 sedans, which were mostly Camaros save for a lone Firebird driven by Tiny Lund and Steve “Yogi” Behr, and two Ford Mustangs.

The 3-liter sports cars were led by two Mirage M6-Fords entered by Gulf Racing for Derek Bell/Howden Ganley (No. 1) and Mike Hailwood/John Watson (No. 2); an Equipe Matra-Simca MS670 entered by the factory driven by Francois Cevert, Jean-Pierre Beltoise, and Henri Pescarolo; a Joest Racing Porsche 908/03 driven by Reinhold Joest, Mario Casoni, and Paul Blancpain; a Porsche 908/02 driven by Rudy Bartling, Harry Bytzek, and Bert Kuehne; and a lone Scuderia Fillipinetti Lola T282-Ford was driven by Riene Wisell, Jean-Louis Lafosse and Hughes de Fierlant.

Also running in the Sports 3000 class were Peter Gregg and Hurley Haywood in the Brumos Porsche Carrera RSR, along with Mark Donahue and George Follmer in the Penske Racing Carrera RSR. The Carrera RSR was in the top class because it was a new model and had a bigger engine than the other 911s in the race, which ran in our Grand Touring +2000 class. We had raced against all of them in the ’70 and ’71 Trans-Am, so feelings of wanting to beat them all were running pretty high in the Budd Corvette team.

There were two untimed practice sessions and three qualifying sessions stretching over Thursday and Friday before the race got underway at 3:00 p.m. on Saturday. The trick was to bring the drivers up to speed at a deliberate pace while scrubbing in tires and brake pads, and checking all the systems to make sure everything was working. And, there was an all-important night practice on Thursday. That would let the drivers get used to the track in the dark and allow the team to aim the lights properly.

Finishing the fuel filler and close out for it on the rear deck proved to be a pain in our list of things to finish at the track. It worked and it was safe, but it was butt ugly. Fortunately the back of the Budd Corvette was black so it all blended in, and from 20 feet away it was just fine. The front spoiler was much more difficult of a project; and it shows in all the photos. Dynamically, the spoiler was fine, but aesthetically it needed a lot of work.

Finally, after five months of thrashing, it was time For Tony to get into our new race car and see what we had. He buckled in for the early session on Thursday morning, and after some brief discussion with Deryl, Mo Carter, and Lee Dykstra about what we wanted to get done, he pulled out of the pits and onto the race track.

Tony spent the first few laps feeling out the controls, brakes, clutch, gearbox, and steering. This is what he recalls: “The Budd Car was unlike any Corvette I had ever driven, that was obvious. The biggest change was having brakes that were very strong, and a chassis that reacted instantly to my control inputs. The engine was like that locomotive Deryl described after looking at the torque curve in Bill King’s shop. It reminded me of Bill Morrison’s ‘rocket’ motor at Talladega the previous August.”

“An equally big change was the new 2.42 gear ratio we were using. After spending five years with the 2.73 gear and the 427 L88 engine at Daytona, I had to learn new shift points all around the track. The neat part was pulling out onto the oval between NASCAR Turn 1 & 2 in second gear. The engine pulled that long gear and built up speed at an amazing rate, but I didn’t have to shift into fourth gear until I was on the back straight after the 31° banking flattened out! I could tell that I had built up big-time speed by then, maybe 165+ mph. By the time I got to the NASCAR Turn 3 on the oval, the engine was pulling nearly 6,000 rpm. After enough laps to get comfortable I pitted and turned the car over to Mo Carter. He was enthused after his stint, and we worked through the session getting tires and spare brake pads scuffed in.”

In the Thursday afternoon practice session, Mo was out in the car and it began to rain so he brought the car in. Fred McKenna had some full-wet R106 Firestones and Tony decided to see how the car worked in the rain. It was actually a good idea because it always seemed to rain during the 24 Hour at some point. Tony had this to say: “I got out on the track and soon realized I had the whole place to myself. My competitors didn’t seem to want to deal with the rain so soon in the proceedings. At Daytona during heavy rain the infield portion of the course is treacherous, with lots of places that puddle and can cause the car to aquaplane. My R106s were doing their job and I quickly got into the groove. The good thing about Daytona in the rain is that the banking, including the long back straight, drains very well. The pavement is like sandpaper and provides traction very close to dry conditions. To the spectator, and sometimes the driver, it can appear horrifying, but to this driver racing in the rain at Daytona is a hoot.”

Tony was having a good time with the track all to himself, and when he decided to pit he found a crew - several crews actually - wide eyed with ear to ear grins on their faces. To a man, 45 years later, they all told the same story. Here is their impression of what transpired when Tony was on the track in the rain, in their own words, starting with Fred McKenna:

“Damp doesn't equal wet. If you'll remember, you were the only car that went out on the track during the practice session where it rained heavily enough that the deep-skid 106's could be tried but not torn up, and some of your best races were wet ones. (Meadowdale for instance.) The car could be heard all around the track and the sound down the back straight was awesome. And that's awesome before the days of Tony Stewart's or Jeff Gordon's awesome.”

PR man Chuck Koch adds to the memory:

“One memory is forever burned into my brain, and that is the practice session when it rained. Everyone else came in when the rain started, but you actually went out; as you said later, a good chance to check out things in the wet. The Budd Corvette was the only car on the track, so it was quiet except for you, a sensation only enhanced by the low cloud cover that served as a sort of natural sound board, isolating and almost amplifying whatever noise there was. As you came off the infield section and accelerated onto the banking in NASCAR Turns 1 and 2, that big old 454 started making the power and emitting the most glorious roar you'd ever hope to hear. The echo chamber of clouds reflected it back towards the pits, and as the car blasted down the back straight, the sound was dopplering off the banking in NASCAR Turns 3 and 4 with increasing frequency as the distance between the banking and the onrushing car rapidly diminished. You were out there alone for several laps, and it was the coolest, most awesome thing to hear, this car literally booming around the place, and the entire crew simply stood there smiling, just enjoying the sound. Several other crews were doing the same.”

And Fred McKenna contributes the epilog to an amazing impression left by the Budd Corvette at the wet Daytona practice in 1973:

“You’ll remember the time that there was a break in the practice session in ’69 – between afternoon and night practice - and the Holman & Moody boys wheeled out the Torino Talladega from their little secret garage for some hot laps on the oval, and the way a car that large (taxi size to them) captured the attention of the foreign crews. They looked like kids on the fence at the zoo with their eyes and mouths wide open. Your practice laps, running solo, had the same effect on the pit lane crowd in ’73. It sounded like a tape from one of the dyno cells or one of the old Riverside Records “Sounds of…” LPs. You remember LPs; they are like CD’s only much bigger!”

After wowing the assembled teams in pit lane, the team took a little break before getting ready to run night practice and discussed where we were with our program. We joked that the engineering and mechanical departments were getting the hang of it, but the drivers needed work. Tony and Mo stood their ground and said that we could go faster if the motor guys could find us another hundred or so horsepower. In reality, Tony and Mo were quickly getting comfortable with our new Budd Corvette, and the crew was beginning to realize just what a good car we had put together. Some quiet confidence was beginning to build, but we had long ago learned that it was best to put our noses to the grindstone and keep working.

The crew rolled “The Monster” over to the Cibie headlight garage to get the aiming of the lights dialed-in and do final checks before Tony and Mo went out for the night practice. When Deryl pulled the Budd car into the pits we noticed a strange pair of green lights on the roof about a foot back from the windshield header. We had always used some form of nighttime ID lights for our cars at Daytona, but usually they were trailer marker lights or something like that. Tony asked Ken Wiedbush and Bill Boskey where they got the lights and they seemed a little nervous, saying: “Um, they are bicycle lights.” They had wired them into the car’s electrical system, but we never did get an official explanation about where they came from.

Night practice went off without any major issues. Tony went out and got comfortable with the lights and the routine of driving in the semi-darkness that is Daytona, and Mo Carter did the same. Tony tells it: “I like night driving and at Daytona, the time between about 2:00 a.m. and dawn is what I refer to as 'the Graveyard Shift.' It seems to go on for an interminable amount of time, but just when you think the night is going to last forever you see that faint white line above the East banking in NASCAR Turn 3 that signals a new dawn, and the hope that you might survive the 24 Hour unscathed.”

We got to the track at 8:00 a.m. the next morning and it actually felt a little strange to have had a decent night's sleep for a change. Our crew had warmed to the task of getting ready to run the race, and had the pit area set up and everything organized by the end of the day.

Tony would handle the qualifying effort and when the session stopped the front row was occupied by the No. 1 Gulf Mirage-Ford of Bell/Ganley with a 1:45.512 lap, and the Matra MS670 of Cevert/Pescarolo/Beltoise. The No. 2 Gulf Mirage and the Scuderia Filipinetti Lola T282 would make up the second row. Tony and Mo shared the third row with the Harry Bytzek Porsche 908/02. Tony had qualified the Budd Corvette sixth with a time of 1:58.895.

Chuck Koch recalls Tony’s qualifying performance: “You qualified 6th on the grid, 1st in GT, at 1:58.895 (I looked it up); the only GT car faster than two minutes. There were five prototypes in front of you, and six behind. The next GT car was about two seconds slower. (That would be the Jerry Thompson/Ike Knupp/Mike Murray Corvette.) Roger Penske had just re-upped with Porsche and was there in the Sport 3000 class for the first time in a while, with a 911 Carrera RSR that Mark Donohue was driving with George Follmer. He was almost four seconds off your pace (2:02.794) and was 6th among the GT cars. So, uncharacteristically, RP’s Porsche was many rows back. Roger was not at the track during practice and qualifying, but I remember that he came up to you on the grid and said, ‘So, Tony, this is the cheatin' Corvette that Mark's been telling me about?’ You allowed as how it was about all you could do to get the car done in time for the race, and that there was no time to do any cheating. As Roger left to find his way to the back of the grid, you looked at me and said, ‘Actually, we're a little bit slower than we were a couple years ago. Roger's been out of GT long enough that's he's forgotten how competitive it is.’ In fact, in 1971 you qualified at 1:57.19.”

We were slower than in the ’71 version of qualifying because of the 2.42 gear we were pulling, and the conservative 5,500 rpm limit we gave ourselves. The long stroke motor was up to the task though, as qualifying times indicate. Tony adds: “The key, to me anyway, was the way the Budd Corvette ran on the straight. Even with our 5,500 rpm rev limit, the car gained speed on the straight like a Great White Shark after a bunch of seals. The other reason we went a little slower in qualifying than before was that nobody was pushing us. Jerry Thompson’s Corvette was the next fastest car in our class, 7th on the grid, but they were nearly 1.5 seconds slower. We didn’t feel the need to push the car in qualifying; if we had, we would have used the 2.73 gear and 6,000 rpm. We felt our chances in the race were very good.”

The 3:00 p.m start of the 24 Hour gave us plenty of time to do everything needed to get ready. It was actually sort of relaxing to get to the track in the morning and know that you had seven plus hours to prepare for the start. The guys working on the car did all the pre-race checks with an outwardly calm tempo. Those in charge of the pit set up had their own routine too. Everybody had a job to do and did it. We had a meeting about noon to discuss final plans with drivers and the guys who would be working the pit stops. Drivers would run two fuel stops and change at the second stop. This would give each driver about three hours in the car, and an adequate rest period before the next stint.

Tony and Mo Carter did their thing with Chuck Koch for the media types who were in attendance. They also schmoozed with the other drivers on the grid as we got closer to the start. The fact that we were on the Grand Touring +2000 pole and sixth on the grid of 57 starters had not escaped their notice. We had made a statement, but we would have to back it up when the green flag waived. We were tense but confident. I will let Chuck Koch have the honor of describing Tony’s run at the start:

“Okay, so the parade laps start and it's kind of funny; here's five low-slung prototypes, then this big hump of a Corvette rumbling in the midst of them, and then more low-slung prototypes behind. It just seemed somehow strange looking, almost incongruous. Then the green flag waves and everyone accelerates away. The first time past there were the high-pitched screams of the leading few prototypes, then this big, roaring, thumping behemoth, and then some more screaming before the next V8 GT car came by. You were 5th the first time past, and 4th the next. It was almost as cool as the solo laps in the rain. There'd be a wheeeeen, wheeeeen, wheeeeen, (or whatever onomatopoeia you use to simulate the sound of the OHC prototypes' engines) as the lead cars went past, then the air would be rent and your chest assaulted as the Budd car thundered by, RRROOOAAARRR, and then some more wheeens. You held 4th for several laps before settling into race pace.”

Tony recalls it this way: “The start of any race is a high stress event for the driver. The 24 Hour is no exception. The mindset for us, back then, was to try to race according to our plan and the track rather than have things degenerate into a street fight with the other cars the way things seem to go in today’s long distance races. I gently worked the brakes and tires up to temperature during the two pace laps. I was surrounded by 3-liter sports cars and tried to ignore them while I was getting my own act together. I wasn’t sure what to expect from the Mirages, Porsches, and Matra sports cars at the start. We didn’t spend any time around them in practice and qualifying since they were much quicker, the pole sitter being more than 13-seconds a lap faster than we were.

Surprise! When we came out of NASCAR Turn 4 to get the green flag, everybody seemed to be on their best behavior going into turn one into the infield; nobody wanted to earn the wrath of their crew by doing something stupid on the pace laps, and the start of a 24 hour race. I consciously kept to my 5,500 rpm red line and expected the sports cars to disappear quickly, but we stayed in a bunch through the infield and onto the banking. Now they’ll disappear, I thought to myself. To my surprise, I passed the Lola T282 of Reine Wisell, and the Porsche 908 of Harry Bytzek, leaving the two Gulf Mirages and the factory Matra in front of me. The lead cars were not leaving me on the long back straight and 31° banking of NASCAR Turns 3 and 4.

Now my mind began to race; fuel I thought, they are fat with fuel and they don’t have any torque. Well, torque compared to my car that is. Once more through the infield and the Budd Corvette wasn’t losing any ground to speak of; any that was lost was quickly made up on the oval. Now I was genuinely conflicted. In one or two corners in the infield during the heat of the start, I had let the rpm drift to 6,000+ and felt the entire character of the car change. There was even some wheel spin coming out of the infield Turn 5, heading for the hairpin leading onto the banking.”

This was no ordinary Corvette, that is for sure. Tony adds: “After all these years, I can now confess to thinking the following as we climbed onto the Daytona banking to start the second lap of the race: ‘I can hammer this thing and drive by these guys like they are tied to a tree and lead this race for a lap or maybe two.’ Sigh! The devil on my left shoulder said to hammer it; but the angel on my right shoulder said to remember the plan and I can win the race. Another trainload of Catholic guilt just left the station. So I stuck to the plan and drove like an altar boy for my first stint and then pitted for fuel.

Everything was running according to plan. We were leading the GT +2000 class and running in the top six overall with no issues. My second stint went like the first, and I handed the car over to Mo Carter around 6:00 p.m. When I got out, the guys were smiling. I think that meant I was doing a good job. We were on schedule, and Mo was doing a great job too. I tried to relax a little in the trailer we had rented for the race and got back to the pits just after Mo had made his first stop. I saw my friend Greg who was on a break from the signal pits. He was grinning from ear to ear, and allowed as to how the Budd Corvette was a 'monster'. Little did he know just how much of a monster it was.”

But remember, this is racing, and racing runs the gamut from the highest of highs to the lowest of lows, in a matter of moments. And sometimes it just flat-out sucks. Shortly after 8:00 p.m. we got the bad news: Race control told our timers that Mo had parked the No. 11 Budd Corvette in the grass just past NASCAR Turn 2 with a reported engine problem. The car was in a safe spot so we couldn’t retrieve it until the next morning. We just stood in the pits with a numb feeling spreading over us. A few minutes later Mo got out of a track vehicle and came over. He said that everything was fine as he was going through the West banking, and then the engine just quit cold. He recognized the massive engine failure, took the car out of gear, and coasted to the grass on the inside of the track. “The Monster” had died somewhat quietly on the back straight, according to Mo. We had completed 101 stinkin’ laps.

For the record, Peter Gregg and Hurley Haywood won the race overall in the Brumos Porsche RSR, completing 670 laps. The N.A.R.T. Ferrari 365 GTB/4 of Milt Minter, Francois Migault, and Claude Bellot-Lena was second with 648 laps. Dave Heinz was third in his Corvette, completing 644 laps. The Grand Touring +2000 cars occupied the first six finishing positions. The first, and only “sports car” Sports 3000 finisher was Harry Bytzek’s 908 Porsche in 12th place. There were only 15 cars classified as finishers out of 57 starters.

We would get some rest before the non-stop drive back to Detroit, but the good night’s sleep didn’t make anybody feel any better about the outcome.

The day after we got back to the shop we pulled the engine out of the Budd Corvette and took it down the street to Bill King’s shop for a teardown and post mortem. Chuck Koch describes the scene at the teardown:

“When the pan was dropped, Bill looked up the cylinder bores and said something like, ‘Well, that would probably do it.’ We all, in turn, got down to look, and were greeted with the sight of the top of the piston staring down at us in the bore. Tony said something about how loud the little man must have screamed. From the bottom of the pan, Bill retrieved the two halves of the con rod that had split neatly right down the middle, starting at the oiling hole drilled on the small end. Bill Howell, an engine engineer from Chevrolet was there, and when he saw the rod, he allowed as how that they had found out the 454 had a harmonic vibration in the 5,500 rpm range which caused the rods to break at the oiling hole. And, in fact, it had been determined that actually no oiling hole was needed at all. Of course, 5,500-5,700 rpm is right where the team had decided to run the motor since, based on experience with the 427, the engine should have lasted forever at such low revs. Tony and Bill thanked Bill Howell for passing the information along so expeditiously, he shrugged and it was sort of agreed that that was racing."

Tony had this to say: “In reality, it was a bitter pill to swallow. For 40+ years I have agonized over the decision to run the engine the way we did at Daytona. I have lost count of the number of times the race scenario has played out in my mind, but it would have been nice to see the result of shifting the car at 6,000 rpm and running the “normal” 2.73 Daytona gear. Oh well.”

It was "just one of them racing deals" as racers like to say.

“The Monster” Corvette had been designed, engineered, built and executed by some of the best minds in the business at that fleeting moment in time. It was a stunning piece of work. And even though things didn’t work out the way we wanted them to, it was worth each and every memorable moment.

The team would gain a measure of solace at Sebring about six weeks later as Tony would put “The Monster” on the overall pole position (it was an all GT field that year). But more on that in next week’s installment. Stay tuned.

(The DeLorenzo Collection)

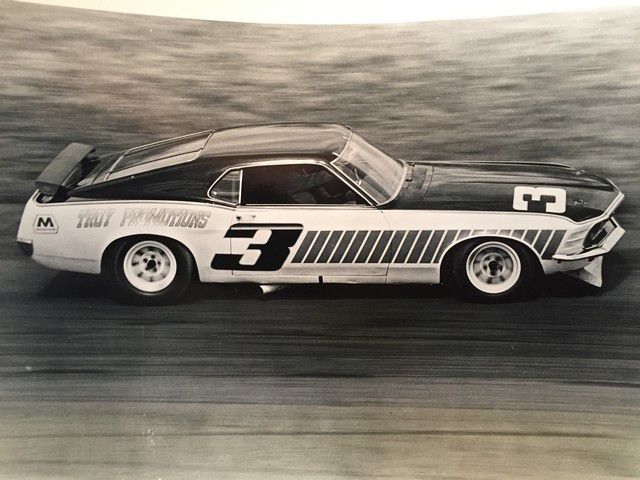

After being marginalized by certain Chevrolet racing operatives, we went out and purchased two Bud Moore Engineering Mustang Trans-Am cars used to win the '70 Trans-Am Championship for Ford and Parnelli Jones. This is how they looked in our new Troy Promotions Inc. livery, designed by the legendary GM designer Randy Wittine, of course.

(The DeLorenzo Collection)

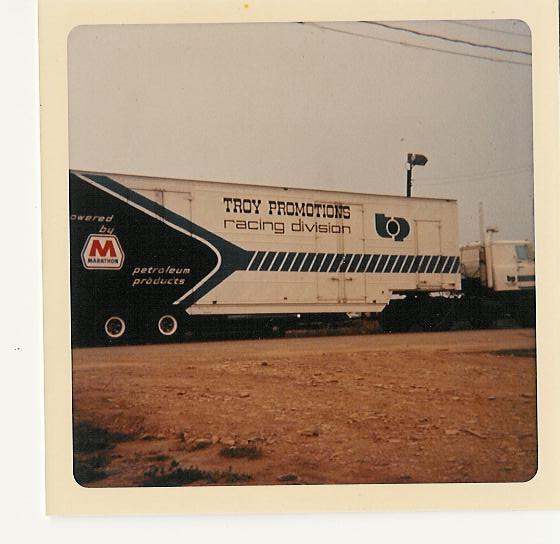

After using up our first trailer, we purchased the trailer used by Dan Gurney's All American Racers team in the 1970 Trans-Am season. This is how it appeared at the first race of the 1971 Trans-Am season at Lime Rock.

(The DeLorenzo Collection)

Pit action at the 1971 Trans-Am race at Mid-Ohio. The TPI team consistently executed its pit stops as fast as Penske Racing that season.

(The DeLorenzo Collection)

The No. 3 TPI Ford Mustang had a great on-track look. There were several models made of it, including a scalextric-usa slot car.

(The DeLorenzo Collection)

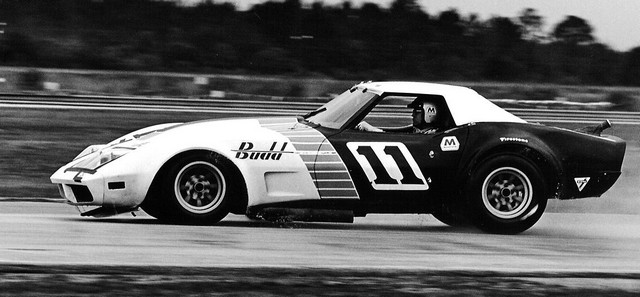

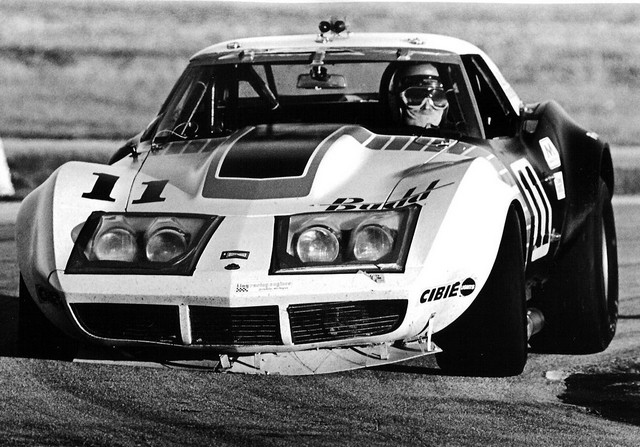

Tony at speed in Bill Morrison's bad ass big-block Corvette in an IMSA/Grand-Am race at the Talladega Superspeedway back in 1972. The lessons learned from that car's engine played into the development of "The Monster."

(Photo by Hal Crocker/The DeLorenzo Collection)

Tony (No. 11 TPI Budd Corvette) made a splash in the rain during a practice session for the Daytona 24 Hour in 1973. Note the shortened side exhaust pipes.

(The DeLorenzo Collection)

Big power, monster torque - a look under the hood at the 467 cu. in. V8 in the Budd Corvette. (The DeLorenzo Collection)

(The DeLorenzo Collection)

The instrument panel was functional and up to the task. Note the Cadillac emblem - it was put there by the boys on the team from Cadillac Engineering who worked on the car.

(Photo by Hal Crocker/The DeLorenzo Collection)

The No. 11 Troy Promotions Inc. Corvette on the east banking at the Daytona International Speedway in 1973.

(Photo by Hal Crocker/The DeLorenzo Collection)

Tony turns "The Monster" on to the banking at Daytona in 1973.

(Photo by Hal Crocker/The DeLorenzo Collection)

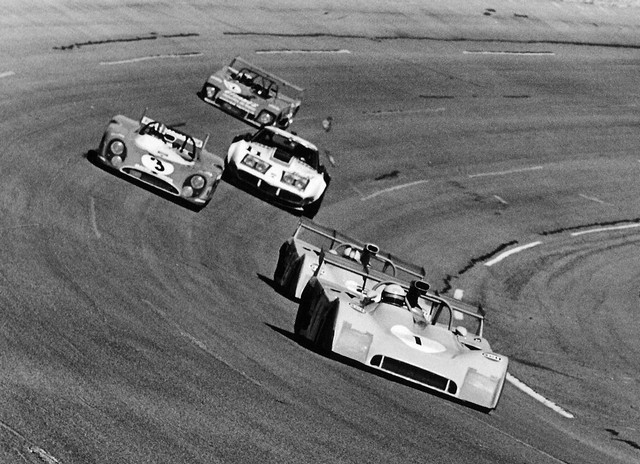

The first few laps of the 1973 Daytona 24 Hour race, with Tony running fourth in "The Monster." The No. 11 TPI Budd Corvette was a brilliantly conceived and executed racing machine, representing the best and the brightest of that era. And with a different gear and a less conservative race strategy, the outcome might have been decidedly different. But then again, Woulda-Coulda-Shouldas count for exactly zero in racing. Thus it was ever so, unfortunately.

Editor's Note: Many of you have seen Peter's references over the years to the Hydrogen Electric Racing Federation (HERF), which he launched in 2007. For those of you who weren't following AE at the time, you can read two of HERF's press releases here and here. And for even more details (including a link to Peter's announcement speech), check out the HERF entry on Wikipedia here. -WG

Publisher's Note: As part of our continuing series celebrating the "Glory Days" of racing, we're proud to present another noteworthy image from the Ford Racing Archives. - PMD

(Courtesy of the Ford Racing Archives)

Daytona Beach, Florida, February 24, 1963. Tiny Lund (No. 21 Wood Brothers English Motors Ford) runs with Freddie Lorenzen (No. 28 Holman-Moody LaFayette Ford) in Turn 3 at the Daytona International Speedway during that year's Daytona 500. Lund would win that day followed by Lorenzen, Ned Jarrett (No. 11 Charles Robinson Burton-Robinson Ford), Nelson Stacy (No. 29 Holman-Moody Ron's Ford Sales Ford) and Dan Gurney (No. 0 Holman-Moody LaFayette Ford). Watch a video here.